---somethin' happening in here, what it is ain't exactly clear ---- Buffalo Springfield - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f5M_Ttstbgs

Teacher Unrest Spreads to Oklahoma, Where Educators Are “Desperate for a Solution”

Link

Last summer, Teresa Dank, a third-grade teacher in Tulsa, Oklahoma, gained national attention after she began panhandling

to raise money for her classroom. Like many other teachers in a state

with some of the lowest education spending in the country, Dank was at

her wit’s end. Her frustration came to a head two weeks ago, following

yet another failed legislative attempt to increase teacher pay. And so

she started an online petition,

asking for signatures from those who would support a walkout by

teachers. Soon another Oklahoma teacher named Alberto Morejon launched a Facebook group to mobilize fellow educators for a walkout, quickly drawing tens of thousands of members.

The increasing momentum for a strike in Oklahoma comes as a strike by West Virginia teachers entered its ninth consecutive school day on Tuesday. State lawmakers, hoping to bring the strike to an end, reached a deal on Tuesday morning to raise all state employee salaries by 5 percent. Oklahoma’s 42,000 teachers make even less than their West Virginian counterparts; in 2016, the average Oklahoma teacher earned $45,276, a salary lower than that of teachers in every state except Mississippi. With no pay increases for Sooner State teachers in a decade, educators have been leaving for greener pastures, moving to neighboring states like Arkansas, New Mexico, Kansas, and Texas. Last May, Shawn Sheehan, Oklahoma’s 2016 Teacher of the Year, announced that he would be moving to Texas for more financial stability.

Strikes by Oklahoma school employees are technically illegal, but educators have found a legal work-around. If school districts shut down, then that’s a work stoppage that doesn’t involve teachers walking off the job. Many superintendents across the state have already come out in support of closing down schools if the teachers decide to move forward with their strike.

Teachers point to a four-day strike from nearly three decades ago, when more than half of Oklahoma educators stayed home from school. This successful 1990 protest prompted the legislature to raise teacher pay, institute class-size limits, and expand kindergarten offerings.

“Nothing else has worked over the last two to three years, so at this point teachers, parents, and community members are desperate for a solution,” said Amber England, a longtime Oklahoma education advocate. “This is what they’re thinking is the last resort. They don’t want to do it, but they really don’t feel like they have any other option.”

But that measure also ended up failing miserably, garnering just over 40 percent of the vote. Republicans in the state opposed taxes going up, and many Democrats also opposed the measure because a sales tax would have hit the poor the hardest.

In 2017, the legislature promised yet again to pass a teacher pay raise, adjourning in the end with nothing to show for it. A measure to raise teacher and state employee salaries funded by a tax on cigarettes, motor vehicle fuel, and beer failed 54-44 in October.

“Time after time, there’s just been terrible cuts, broken promises, and no legislative action or leadership,” England told The Intercept.

Just like in Kansas, Oklahoma’s leaders have been slashing taxes, finding that this then leaves them with less money to fund basic government services.

Aside from reducing income taxes for its wealthiest citizens in 2013, Oklahoma legislators voted in 2014 to extend major oil industry tax cuts that were set to expire in 2015. The drilling tax, known as the “gross production tax,” or GPT, had been set at 7 percent in the 1970s, but in the early 1990s, when horizontal drilling first came on the scene, the then-Democratic controlled legislature reduced it down to 1 percent, to help encourage experimentation with the new technology.

The GPT was supposed to return back to 7 percent in 2015, but Republicans instead made the tax cuts permanent at 2 percent, a notably lower rate than other oil-producing states.

But when legislators voted on the package in mid-February, it too failed, with 17 Democrats and 18 Republicans voting against the measure. Some Republicans argued this was Oklahoma’s last real shot at reaching a compromise this year, but other Democrats said they don’t buy that this is the best deal they could reach.

Rep. Forrest Bennett, a first-term Democrat representing Oklahoma City, was among those who voted against the Step Up plan.

“There was a hell of a lot of pressure on us to pass it, and I’ve gotten a lot of shit for voting no, but this package was pretty flawed from the start,” he told The Intercept. Bennett noted that aside from teacher pay increases, the Step Up deal contained a number of regressive taxes and pushed only for doubling the GPT up to 4 percent.

In October, a new nonprofit, Restore Oklahoma Now, formed to push for a 2018 ballot measure that would hike the GPT back up to 7 percent and direct the majority of new revenue to schools and teachers. That effort is being led by Thompson, the former OIPA president.

“We felt we needed to get GPT to at least 5 percent,” Bennett explained. “We were being dictated to by this private business owner group, and as long as that 7 percent ballot initiative is looming, we think we will have more opportunities to push for alternatives.”

England, who had been helping the Oklahoma Education Association mobilize support for the Step Up plan, emphasized that it’s been increasingly difficult to reach any sort of bipartisan agreement. “Compromise is not the politically correct position anymore,” she told The Intercept.

Different dates are floating around for a potential strike. One scenario is to strike on April 2, the same time that students are scheduled to take their mandatory standardized tests. Failing to take those tests could mean Oklahoma sacrifices millions of dollars in federal funds. Organizers are calling this the “nuclear option.” Another possibility is to shut down schools the week following spring break, which would be the week before standardized testing. The Oklahoma Education Association plans to hold a press conference Thursday afternoon to unveil a “detailed revenue package and a statewide closure strategy.” NewsOK, a local news outlet, reported that nearly 80 percent of respondents to an online survey administered by the Oklahoma Educators Association voiced support for school closures to force lawmakers to increase educational investments.

Thompson, the leader behind the GPT ballot initiative, worries a teacher walkout will damage public support for educators in the state. “I think a majority of teachers understand what we’re trying to do [with our initiative], but their morale is very low, and they are beyond frustrated,” he said. He acknowledges, though, that his concerns “are falling on deaf ears” and that “teachers are ready to try anything.”

For his part, Thompson thinks the ballot initiative he’s leading stands a better shot at passage than the failed 2016 penny tax. “Teachers have gone two more years without a pay raise, and the public has been talking about it for all this time now,” he said. “There is just more public support for a teacher raise than two years ago.”

Their ballot initiative isn’t a done deal yet, though; they haven’t even begun collecting the necessary 123,000 signatures. Last week, they defended their ballot initiative at Oklahoma’s Supreme Court, and now they’re waiting for the court’s approval to move forward.

“The court can take as long as they please to give us a decision on whether we’re valid or whether we’re kicked to the curb,” Thompson explained. “We’re not officially a ballot initiative until we get their approval, but we’re feeling confident.”

Democrats remain convinced that all the mounting pressure will create more opportunities for lawmakers to push forward alternative revenue packages this legislative season. Bennett said the threat of a 7 percent GPT ballot initiative, a statewide teacher walkout, and a potential blue wave for Democrats across the country in November, will help keep pressure up in the legislature.

“The Step Up coalition made people feel like their deal was the last shot, but it’s not,” he said. “What they did do was engage a lot of people, and now a lot more are really frustrated and are paying attention.”

The increasing momentum for a strike in Oklahoma comes as a strike by West Virginia teachers entered its ninth consecutive school day on Tuesday. State lawmakers, hoping to bring the strike to an end, reached a deal on Tuesday morning to raise all state employee salaries by 5 percent. Oklahoma’s 42,000 teachers make even less than their West Virginian counterparts; in 2016, the average Oklahoma teacher earned $45,276, a salary lower than that of teachers in every state except Mississippi. With no pay increases for Sooner State teachers in a decade, educators have been leaving for greener pastures, moving to neighboring states like Arkansas, New Mexico, Kansas, and Texas. Last May, Shawn Sheehan, Oklahoma’s 2016 Teacher of the Year, announced that he would be moving to Texas for more financial stability.

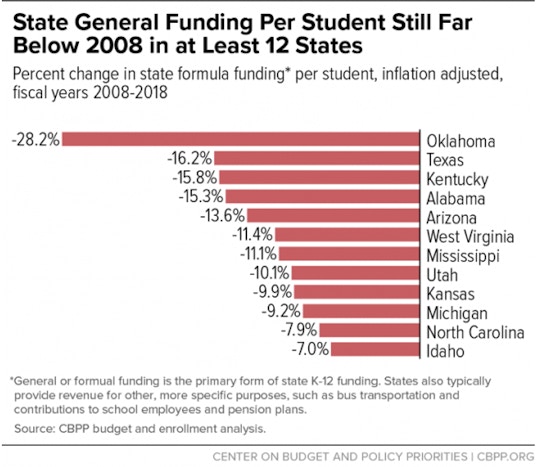

Per-pupil spending in Oklahoma stands at $8,075, among the lowest in the country.As it so often goes, when times are tough for teachers, times are also tough for students. Per-pupil spending in Oklahoma stands at $8,075, among the lowest in the country and lower than all of Oklahoma’s neighboring states. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities puts Oklahoma’s cuts to general education funding since the recession as the highest in the nation, with 28 percent of the state’s per-pupil funding cut over the last decade. Things have gotten so bad that nearly 100 school districts across the state hold classes just four days a week to save money.

Strikes by Oklahoma school employees are technically illegal, but educators have found a legal work-around. If school districts shut down, then that’s a work stoppage that doesn’t involve teachers walking off the job. Many superintendents across the state have already come out in support of closing down schools if the teachers decide to move forward with their strike.

Teachers point to a four-day strike from nearly three decades ago, when more than half of Oklahoma educators stayed home from school. This successful 1990 protest prompted the legislature to raise teacher pay, institute class-size limits, and expand kindergarten offerings.

“Nothing else has worked over the last two to three years, so at this point teachers, parents, and community members are desperate for a solution,” said Amber England, a longtime Oklahoma education advocate. “This is what they’re thinking is the last resort. They don’t want to do it, but they really don’t feel like they have any other option.”

Why Aren’t Teachers Getting a Raise?

Educators were optimistic that things were going to change in 2016. The Republican-controlled legislature promised it’d pass a teacher pay increase, but in the end they failed to get anything done. Later that same year, a high-profile ballot initiative went before voters to increase the state sales tax by 1 percent, to give all teachers a $5,000 pay increase.But that measure also ended up failing miserably, garnering just over 40 percent of the vote. Republicans in the state opposed taxes going up, and many Democrats also opposed the measure because a sales tax would have hit the poor the hardest.

In 2017, the legislature promised yet again to pass a teacher pay raise, adjourning in the end with nothing to show for it. A measure to raise teacher and state employee salaries funded by a tax on cigarettes, motor vehicle fuel, and beer failed 54-44 in October.

“Time after time, there’s just been terrible cuts, broken promises, and no legislative action or leadership,” England told The Intercept.

Just like in Kansas, Oklahoma’s leaders have been slashing taxes, finding that this then leaves them with less money to fund basic government services.

Aside from reducing income taxes for its wealthiest citizens in 2013, Oklahoma legislators voted in 2014 to extend major oil industry tax cuts that were set to expire in 2015. The drilling tax, known as the “gross production tax,” or GPT, had been set at 7 percent in the 1970s, but in the early 1990s, when horizontal drilling first came on the scene, the then-Democratic controlled legislature reduced it down to 1 percent, to help encourage experimentation with the new technology.

Oklahoma’s leaders have been slashing taxes, finding that this then leaves them with less money to fund basic government services.Mickey Thompson, who worked as the president of Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association between 1991 and 2005, told The Intercept that the GPT reduction was important back then because horizontal drilling was “really new, untested, unproven, and expensive.” Thompson helped push for the tax reduction in the ’90s, but today has become one of the state’s most vocal advocates for raising it back up to 7 percent, because, he said, by now everyone knows that horizontal drilling easily pays for itself. “These cuts were never supposed to be permanent,” Thompson said.

The GPT was supposed to return back to 7 percent in 2015, but Republicans instead made the tax cuts permanent at 2 percent, a notably lower rate than other oil-producing states.

The Step Up Plan

Following all the legislative failures and the ballot measure failure, a group of influential business leaders in Oklahoma got together in December to formulate a last-ditch effort to push something through. The elite bipartisan coalition, dubbed Step Up Oklahoma, unveiled their proposals in January, advocating modest revenue hikes on GPT, motor fuel, cigarettes, and eliminating a few income tax deductions. Hailed as a grand compromise, the Step Up plan would have generated enough revenue to give all teachers a $5,000 pay raise. All five of Oklahoma’s former living governors endorsed the plan, as did the state’s teachers union.But when legislators voted on the package in mid-February, it too failed, with 17 Democrats and 18 Republicans voting against the measure. Some Republicans argued this was Oklahoma’s last real shot at reaching a compromise this year, but other Democrats said they don’t buy that this is the best deal they could reach.

Rep. Forrest Bennett, a first-term Democrat representing Oklahoma City, was among those who voted against the Step Up plan.

“There was a hell of a lot of pressure on us to pass it, and I’ve gotten a lot of shit for voting no, but this package was pretty flawed from the start,” he told The Intercept. Bennett noted that aside from teacher pay increases, the Step Up deal contained a number of regressive taxes and pushed only for doubling the GPT up to 4 percent.

In October, a new nonprofit, Restore Oklahoma Now, formed to push for a 2018 ballot measure that would hike the GPT back up to 7 percent and direct the majority of new revenue to schools and teachers. That effort is being led by Thompson, the former OIPA president.

“We felt we needed to get GPT to at least 5 percent,” Bennett explained. “We were being dictated to by this private business owner group, and as long as that 7 percent ballot initiative is looming, we think we will have more opportunities to push for alternatives.”

England, who had been helping the Oklahoma Education Association mobilize support for the Step Up plan, emphasized that it’s been increasingly difficult to reach any sort of bipartisan agreement. “Compromise is not the politically correct position anymore,” she told The Intercept.

Strike As a Last Resort

For many teachers, the legislature’s failure to pass the Step Up plan was the last straw. Dank launched her petition a week after the failed vote, capitalizing on the frustration of thousands of teachers whose classrooms have been underfunded for far too long.Different dates are floating around for a potential strike. One scenario is to strike on April 2, the same time that students are scheduled to take their mandatory standardized tests. Failing to take those tests could mean Oklahoma sacrifices millions of dollars in federal funds. Organizers are calling this the “nuclear option.” Another possibility is to shut down schools the week following spring break, which would be the week before standardized testing. The Oklahoma Education Association plans to hold a press conference Thursday afternoon to unveil a “detailed revenue package and a statewide closure strategy.” NewsOK, a local news outlet, reported that nearly 80 percent of respondents to an online survey administered by the Oklahoma Educators Association voiced support for school closures to force lawmakers to increase educational investments.

Thompson, the leader behind the GPT ballot initiative, worries a teacher walkout will damage public support for educators in the state. “I think a majority of teachers understand what we’re trying to do [with our initiative], but their morale is very low, and they are beyond frustrated,” he said. He acknowledges, though, that his concerns “are falling on deaf ears” and that “teachers are ready to try anything.”

For his part, Thompson thinks the ballot initiative he’s leading stands a better shot at passage than the failed 2016 penny tax. “Teachers have gone two more years without a pay raise, and the public has been talking about it for all this time now,” he said. “There is just more public support for a teacher raise than two years ago.”

“Teachers have gone two more years without a pay raise, and the public has been talking about it for all this time now.”Thompson also thinks the fact that his proposed ballot initiative would raise revenue without raising taxes on everyone else will help secure its passage. “Conservatives don’t want to raise state sales tax, liberals don’t want a regressive tax, but our deal is not a sales tax — it’s a tax on the oil and gas industry, trying to take away their sweetheart deal that was passed 20 years ago,” he said.

Their ballot initiative isn’t a done deal yet, though; they haven’t even begun collecting the necessary 123,000 signatures. Last week, they defended their ballot initiative at Oklahoma’s Supreme Court, and now they’re waiting for the court’s approval to move forward.

“The court can take as long as they please to give us a decision on whether we’re valid or whether we’re kicked to the curb,” Thompson explained. “We’re not officially a ballot initiative until we get their approval, but we’re feeling confident.”

Democrats remain convinced that all the mounting pressure will create more opportunities for lawmakers to push forward alternative revenue packages this legislative season. Bennett said the threat of a 7 percent GPT ballot initiative, a statewide teacher walkout, and a potential blue wave for Democrats across the country in November, will help keep pressure up in the legislature.

“The Step Up coalition made people feel like their deal was the last shot, but it’s not,” he said. “What they did do was engage a lot of people, and now a lot more are really frustrated and are paying attention.”

Top photo: Students at Edison Preparatory School

stage a walkout to protest the lack of funding for teachers at the

school in Tulsa, Okla., Wednesday, Feb. 14, 2018.

We depend on the support of readers like you to help keep our nonprofit newsroom strong and independent. Join Us

Is Trump more anti union than Obama was? Seems to me the "Right To Work" states proliferated under Barack.

ReplyDeleteAlso! You would think the so called left would support economic nationalism. Trumka does.

I think the real left like Bernie etc does support aspects. Trump makes some sense to me at times. Your priobkem is you don't differentiate the left and confuse liberals with the left. The NY Times MSNBC etc are not left but neo liberals. As are our union leaders. Watch West Virginia Oklahoma etc as Teachers in trump territory revolt.

ReplyDeleteI'm not confusing neo liberalism with what the left to me . They were the workers grounded in economic issues. Forty hour week. fighting capitalism. Living wages, and good work conditions. Anti war (because all wars are bankers wars. The so called left are the cultural, social justice warriors, who have abandoned economic justice for politcal correctness.

ReplyDeleteLeave it to History and the Gods of Irony to throw a curve at everyone, especially #resistance liberals: how are they going to cope with the fact that so many "deplorable" Trump-voting teachers are engaging in far more risky and militant actions, which will provide far more concrete material benefits to working people, than missing brunch for a demonstration and wearing a pussy hat?

ReplyDeleteMy guess is that they will do what they always do when thrown a curve: they'll whiff.

Maybe the Trump voters/strikers are against the "swamp"- entrenched politicians who are not helping improved their constituent's lives. And lets face it, the contract offered to the WV teachers was horrible-can you imagine getting a health insurance break only if you wear a device and reveal your personal health information?

ReplyDelete