When Republicans pivoted to the Southern strategy in the 1960s — uniting rich and poor whites on the premise that they’d always have racial superiority — the Democrats positioned their party as a refuge for everyone else. Identity, consequently, has become centrally important to liberals. It’s not just a useful way to frame experiences which stem from broadly shared characteristics, nor is its political relevance limited to its significant organizing value. Today, identities other than white, cis, straight, and male are foundational to the Democratic Party’s understanding of itself and its ability to persist. Like the clumsy signifier “people of color,” the party defines itself via its relationship to a white male status quo.....

.... https://theintercept.com/2018/08/26/beware-the-race-reductionist/

A hostage situation

has emerged on the left. And progressive policies like “Medicare for

All,” a $15 minimum wage, free public education, a “Green New Deal,” and

even net neutrality, are the captives.

The captors? Bad-faith claims of bigotry.

According to an increasingly popular narrative among the center-left, a dispiriting plurality of progressives are “class reductionists” — people who believe that economic equality is a cure-all for societal ills, and who, as a result, would neglect policy prescriptions which seek to remedy identity-based disparities.

Of course, race and class are so interwoven that any political project that aims to resolve one while ignoring the other does a disservice to both. As Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., presumptive leader of the progressive movement, put it this spring when I asked him about the never-ending race versus class debates: “It’s not either-or. It’s never either-or. It’s both.”

The fear that identity-based issues might be “thrown under the bus” in favor of more populist, “universal” policies is legitimate: The Democratic Party has certainly done as much in the recent past for causes less noble than class equality. But the irony is that anxiety over class reductionism has led some to defensively embrace an equally unproductive and regressive ideology: race reductionism.

If you’re #online, like I am, you’re probably already familiar with the main argument. It goes something like this: If a policy doesn’t resolve racism “first,” it’s at worst, racist and at best, not worth pursuing.

According to one popular iteration of this theme, “Medicare for All” is presumptively racist or sexist because it won’t eliminate discriminatory point-of-service care or fully address women’s reproductive needs if it’s not thoughtfully designed. Perhaps you remember Rep. James Clyburn’s claim that a free college and university plan would “destroy” historically black colleges and universities. Maybe you’ve heard that the minimum wage is “racist” because it “Kills Jobs and Doesn’t Help the Poor,” or that it’s an act of privilege to care about Wall Street corruption, because only the wealthy could possibly mind what the banks do with the mortgages and pensions of millions of Americans. Perchance you’ve even been pitched on the incredible notion that rooftop solar panels hurt minority communities.

Libertarian journalist Conor Friedersdorf recently entered the fray with a piece titled, “Democratic Socialism Threatens Minorities.” His argument? That “top-down socialism” (which progressives want just about as badly as they want top-down capitalism) would create a tyranny of the majority and put minorities at risk.

Completely ignoring the market failures of our current system, and eliding the widespread prejudice and violence black Americans face under capitalism, he concern-trolls by imagining a world in which black women struggle to find suitable hair products. Of course, this is a world we already live in.

Friedersdorf, though, was merely building an addition on a house of cards first constructed by Hillary Clinton during the 2016 presidential primary campaign: “If we broke up the big banks tomorrow,” she famously asked, “would that end racism? Would that end sexism? Would that end discrimination against the LGBT community? Would that make people feel more welcoming to immigrants overnight?”

It was a daring and adroit deception: Ignore this structural salve that would upset the status quo, she implied, because it won’t resolve that more personal, more visceral issue which goes straight to the heart of your identity.

Notice that this trick is aimed at policies which would threaten significant corporate or entrenched interests: the insurance industry, the banking industry, the energy sector, lenders. As the University of California, Berkeley, law professor and leading scholar on race Ian Haney-López observed as we discussed the motives behind this framing, mainstream Democrats, like Republicans, “are funded by large donors. Of course they’re concerned about the interests of the top 1 percent.” It’s almost as if the real agenda here isn’t ending racism, but deterring well-meaning liberals from policies that would upset the Democratic Party’s financial base.

African-Americans are disproportionately victimized by predatory lending, and as a result, we were among the worst affected by the 2008 housing crisis (from which the bottom still hasn’t recovered). Of course, the goal of breaking up banks was to avoid a repeat of the collapse which wiped out 40 percent of black wealth — hardly an incidental issue to African-Americans, who rank the economy, jobs, health care, and poverty above race relations when asked to rate our chief political concerns.

Clyburn’s claim that free college and university would “kill” historically black colleges is similarly a misdirection. HBCUs are facing a funding squeeze and might suffer somewhat if tuition-paying applicants go elsewhere. But Clyburn’s defense of black institutions ignores that black students have the most to gain from college debt relief.

Although there is a black-white college graduation gap, black Americans actually apply to and enroll in college at higher rates than white Americans. Why don’t we matriculate? An inability to pay ranks high among the reasons. And black students carry a disproportionate amount of scholastic debt — more than any other group. The idea that free college would hurt HBCUs is intended to suggest it’s “bad for blacks,” and therefore regressive (or even racist). Given that the opposite is true, it would be easy to interpret Clyburn’s spin as cynical politicking against the interests of the very community he’s presumed to faithfully represent. Affording him the benefit of the doubt earned by his storied legacy of advocacy for the black community, his comments were, at best, a mistake.

Moreover, although immigration is coded as the “Hispanic issue” by the media, only 1 in 10 Latinos are undocumented, while 1 in 3 non-elderly Hispanics are uninsured — that’s the largest uninsured demographic group in the country.

Over-policing is a critical issue, but while approximately 1 in 6 blacks will be incarcerated in our lifetimes, 1 in 4 non-elderly black Americans is uninsured — that’s compared to 13 percent of non-Hispanic white Americans. Even the Black Lives Matter platform, which calls for universal health care, recognizes that health care is not a peripheral issue, but an existential one for black Americans. The reason it’s not perceived as a “person of color issue” is a matter of marketing, not substance.

So will “Medicare for All” cure racism? No. Will it completely eliminate point-of-care discrimination? It won’t. But neither will doubling down on the status quo. Those who admonish these broad economic policies on the grounds that they won’t end bigotry rarely, if ever, propose alternatives that will; nor do they suggest reforms to make flawed universal programs more perfect. This fact, more than anything, exposes the bad faith motives of at least some race reductionists.

Our Revolution president and former Bernie Sanders surrogate Nina Turner described race reductionism as “ludicrous.” “Identity can be used in a positive way to say, ‘Hey, we must recognize that there’s an undergirding concern across all issues in this country,’” for which race is a “major variable,” she told me. “But it is entirely another different story to say we’re going to use some of the most progressive ideas and advancements in this country and say we can’t do them because they hurt [marginalized people]. To me, it’s just asinine.”

She’s right.

It was not always this way. Before the 1980s, the party of the left was the party of labor, and the civil rights movements of the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s were inextricably linked to class. A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin collaborated on the 1966 “Freedom Budget for All Americans,” which attacked black poverty by addressing its source: a paucity of well-paying jobs for low-skilled workers. Colloquially described as the March on Washington, the historic rally’s official name was the March for Jobs and Freedom. And five years later, Martin Luther King Jr. was famously murdered after declaring a war on poverty and U.S. imperialism — far-reaching and institutionally threatening movements that implicated not just how resources were distributed across racial lines, but the legitimacy of our capitalist economic system itself.

The captors? Bad-faith claims of bigotry.

According to an increasingly popular narrative among the center-left, a dispiriting plurality of progressives are “class reductionists” — people who believe that economic equality is a cure-all for societal ills, and who, as a result, would neglect policy prescriptions which seek to remedy identity-based disparities.

Of course, race and class are so interwoven that any political project that aims to resolve one while ignoring the other does a disservice to both. As Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., presumptive leader of the progressive movement, put it this spring when I asked him about the never-ending race versus class debates: “It’s not either-or. It’s never either-or. It’s both.”

The fear that identity-based issues might be “thrown under the bus” in favor of more populist, “universal” policies is legitimate: The Democratic Party has certainly done as much in the recent past for causes less noble than class equality. But the irony is that anxiety over class reductionism has led some to defensively embrace an equally unproductive and regressive ideology: race reductionism.

If you’re #online, like I am, you’re probably already familiar with the main argument. It goes something like this: If a policy doesn’t resolve racism “first,” it’s at worst, racist and at best, not worth pursuing.

According to one popular iteration of this theme, “Medicare for All” is presumptively racist or sexist because it won’t eliminate discriminatory point-of-service care or fully address women’s reproductive needs if it’s not thoughtfully designed. Perhaps you remember Rep. James Clyburn’s claim that a free college and university plan would “destroy” historically black colleges and universities. Maybe you’ve heard that the minimum wage is “racist” because it “Kills Jobs and Doesn’t Help the Poor,” or that it’s an act of privilege to care about Wall Street corruption, because only the wealthy could possibly mind what the banks do with the mortgages and pensions of millions of Americans. Perchance you’ve even been pitched on the incredible notion that rooftop solar panels hurt minority communities.

Libertarian journalist Conor Friedersdorf recently entered the fray with a piece titled, “Democratic Socialism Threatens Minorities.” His argument? That “top-down socialism” (which progressives want just about as badly as they want top-down capitalism) would create a tyranny of the majority and put minorities at risk.

Completely ignoring the market failures of our current system, and eliding the widespread prejudice and violence black Americans face under capitalism, he concern-trolls by imagining a world in which black women struggle to find suitable hair products. Of course, this is a world we already live in.

Friedersdorf, though, was merely building an addition on a house of cards first constructed by Hillary Clinton during the 2016 presidential primary campaign: “If we broke up the big banks tomorrow,” she famously asked, “would that end racism? Would that end sexism? Would that end discrimination against the LGBT community? Would that make people feel more welcoming to immigrants overnight?”

It was a daring and adroit deception: Ignore this structural salve that would upset the status quo, she implied, because it won’t resolve that more personal, more visceral issue which goes straight to the heart of your identity.

Notice that this trick is aimed at policies which would threaten significant corporate or entrenched interests: the insurance industry, the banking industry, the energy sector, lenders. As the University of California, Berkeley, law professor and leading scholar on race Ian Haney-López observed as we discussed the motives behind this framing, mainstream Democrats, like Republicans, “are funded by large donors. Of course they’re concerned about the interests of the top 1 percent.” It’s almost as if the real agenda here isn’t ending racism, but deterring well-meaning liberals from policies that would upset the Democratic Party’s financial base.

It’s almost as if the real agenda here isn’t ending racism, but deterring well-meaning liberals from policies that would upset the Democratic Party’s financial base.The cruel irony is that, as much as it wouldn’t have ended racism, breaking up the banks and properly regulating them would have a positive effect on the economic, and consequently, the social status of black and Hispanic Americans. Banks, left to their own devices, systematically give blacks worse loans with higher interest rates than whites with worse credit histories. Yet there was little talk of those racial impacts when, this spring, 33 Democrats — including nine Congressional Black Caucus members — joined with Republicans to roll back protections contained in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act.

African-Americans are disproportionately victimized by predatory lending, and as a result, we were among the worst affected by the 2008 housing crisis (from which the bottom still hasn’t recovered). Of course, the goal of breaking up banks was to avoid a repeat of the collapse which wiped out 40 percent of black wealth — hardly an incidental issue to African-Americans, who rank the economy, jobs, health care, and poverty above race relations when asked to rate our chief political concerns.

Clyburn’s claim that free college and university would “kill” historically black colleges is similarly a misdirection. HBCUs are facing a funding squeeze and might suffer somewhat if tuition-paying applicants go elsewhere. But Clyburn’s defense of black institutions ignores that black students have the most to gain from college debt relief.

Although there is a black-white college graduation gap, black Americans actually apply to and enroll in college at higher rates than white Americans. Why don’t we matriculate? An inability to pay ranks high among the reasons. And black students carry a disproportionate amount of scholastic debt — more than any other group. The idea that free college would hurt HBCUs is intended to suggest it’s “bad for blacks,” and therefore regressive (or even racist). Given that the opposite is true, it would be easy to interpret Clyburn’s spin as cynical politicking against the interests of the very community he’s presumed to faithfully represent. Affording him the benefit of the doubt earned by his storied legacy of advocacy for the black community, his comments were, at best, a mistake.

Moreover, although immigration is coded as the “Hispanic issue” by the media, only 1 in 10 Latinos are undocumented, while 1 in 3 non-elderly Hispanics are uninsured — that’s the largest uninsured demographic group in the country.

Over-policing is a critical issue, but while approximately 1 in 6 blacks will be incarcerated in our lifetimes, 1 in 4 non-elderly black Americans is uninsured — that’s compared to 13 percent of non-Hispanic white Americans. Even the Black Lives Matter platform, which calls for universal health care, recognizes that health care is not a peripheral issue, but an existential one for black Americans. The reason it’s not perceived as a “person of color issue” is a matter of marketing, not substance.

So will “Medicare for All” cure racism? No. Will it completely eliminate point-of-care discrimination? It won’t. But neither will doubling down on the status quo. Those who admonish these broad economic policies on the grounds that they won’t end bigotry rarely, if ever, propose alternatives that will; nor do they suggest reforms to make flawed universal programs more perfect. This fact, more than anything, exposes the bad faith motives of at least some race reductionists.

Our Revolution president and former Bernie Sanders surrogate Nina Turner described race reductionism as “ludicrous.” “Identity can be used in a positive way to say, ‘Hey, we must recognize that there’s an undergirding concern across all issues in this country,’” for which race is a “major variable,” she told me. “But it is entirely another different story to say we’re going to use some of the most progressive ideas and advancements in this country and say we can’t do them because they hurt [marginalized people]. To me, it’s just asinine.”

She’s right.

It was not always this way. Before the 1980s, the party of the left was the party of labor, and the civil rights movements of the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s were inextricably linked to class. A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin collaborated on the 1966 “Freedom Budget for All Americans,” which attacked black poverty by addressing its source: a paucity of well-paying jobs for low-skilled workers. Colloquially described as the March on Washington, the historic rally’s official name was the March for Jobs and Freedom. And five years later, Martin Luther King Jr. was famously murdered after declaring a war on poverty and U.S. imperialism — far-reaching and institutionally threatening movements that implicated not just how resources were distributed across racial lines, but the legitimacy of our capitalist economic system itself.

But those days are behind us, killed by corporate interests who feared the people’s momentum and derived a strategy to defeat it. Attacks on labor laws gutted unions just as people of color were gaining access to them and reaping incredible benefits

from collective action. And following the embarrassing loss of George

McGovern in the 1972 presidential election, the Democratic Party

committed to corporations as a more reliable source of support. After

all, with the right staking out their claim as pro-white so clearly, where did the more melanated “base” have to go?

When Republicans pivoted to the Southern strategy in the 1960s — uniting rich and poor whites on the premise that they’d always have racial superiority — the Democrats positioned their party as a refuge for everyone else. Identity, consequently, has become centrally important to liberals. It’s not just a useful way to frame experiences which stem from broadly shared characteristics, nor is its political relevance limited to its significant organizing value. Today, identities other than white, cis, straight, and male are foundational to the Democratic Party’s understanding of itself and its ability to persist. Like the clumsy signifier “people of color,” the party defines itself via its relationship to a white male status quo. The coalition, by its very nature, depends on it.

No wonder, then, that identity has become such a lightning rod and critiques of identity politics are so polarizing.

Just look at presumed 2020 hopeful Sen. Kamala Harris’s recent defense of identity politics at the Netroots conference earlier this month.

Seeming to either misunderstand or ignore the critique of identity politics from the left, she argued that the term “identity politics” is used to “divide and it is used to distract. Its purpose is to minimize and marginalize issues that impact all of us.” “It is used to try to shut us up,” she said.

This is certainly true of the political right, which generally rejects identity politics because acknowledging its validity would require them to admit that identities are politicized in response to systemic oppression (which they deny is real), rather than a rejection of individualism.

But the left’s critique of identity politics is not really a critique of identity politics at all, but of the cynical weaponization of identity for political ends. By conflating the two, Harris managed to delegitimize the left’s critique, and strengthen the Democratic Party’s ability to continue to weaponize identity with impunity — whether or not that was her intent.

The root of why some Democrats have adopted this approach feels obvious. Faced with a challenge from the left, the Democratic Party’s usual tactic of comparing itself favorably to Republicans, doesn’t work. Where the establishment offered a $12 minimum wage in 2016, Bernie Sanders argued that $15 was better. When Hillary Clinton sought to protect the ACA, Sanders said it didn’t go far enough.

In her 2017 book “What Happened,” Clinton was explicit about how frustrating she found running against Sanders to be:

But some still employ a mixed strategy, which pairs a shift to the left with an attack on progressivism under the pretext of anti-bigotry. This needs to end, before it ends badly.

Now, the concern that broad-based material policies will replicate, reinforce, or worsen patterns of discrimination is legitimate. It is true that in the past, “universal” programs have been distributed in an inequitable and, at times, racist manner. But that’s not a reason to forestall initiatives aimed at economic equality until some far off time at which racism is cured. Rather, it’s incentive to improve upon them.

Rhiana Gunn-Wright, the policy director for former Michigan gubernatorial candidate Dr. Abdul El-Sayed and the brains behind his comprehensive suite of policy proposals, understands this. In a recent interview, she explained that she takes an “intersectional” approach to policy — a reference to Columbia University law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw’s insight that identities intersect, overlap, and diversify the priorities of individuals within broad identity-group categories.

Gunn-Wright believes that “universal” programs are rightly criticized when they adopt a rising-tide-raises-all-ships philosophy, which can ignore or reinforce disparities across groups. But she says that policymakers can work to avoid that outcome. “The analysis of intersectionality was all about how systems are designed with either a deep inattention to all identities or attention to one identity at a time, and therefore ignoring people who lived at the intersections of those identities,” she told me. But that’s a design problem — not an argument against broad economic programs.

“I think it’s very interesting intersectionality has become such a buzzword now, and you can tell a lot of people have picked it up without ever reading the black women who created the concept,” Gunn-Wright said. “I can never imagine Kimberlé Crenshaw being like: ‘You know what? We definitely should not have single payer until we figure out race.’”

“We think that race, in particular, is a purely social issue and not connected to economics or reproductive justice or criminal justice,” said Gunn-Wright, arguing that, in fact, both class and race are always part of the equation. “I think identities are incredibly important and shape the way we move throughout the world, and they shape the way that people treat us and the way our government treats us. … It’s just been deployed in this way that shuts down progress instead of embracing it, and also assumes in a very strange way that black people wouldn’t want this sort of progress, or wouldn’t benefit from it.”

Touré Reed, professor of 20th century U.S. and African-American history at Illinois State University, observed that the presumption that black Americans aren’t equally or more invested in economic interventions as white Americans is “pregnant, of course, with class presumptions,” which work well for the black and Latinx professional middle class — many of whom play a significant role in defining public narratives via their work in politics or media. Since “the principal beneficiaries of universal policies would be poor and working-class people who would disproportionately be black and brown,” he told me, “dismissing such policies on the grounds that they aren’t addressing systemic racism is a sleight of hand of sorts.”

None of this is to say that in every scenario, race, gender, sexuality, and class are equal inputs. Affluent black athletes are still tackled by cops despite their wealth, and black Harvard professors are arrested trying to unlock their own front doors. But the fact that racism hurts even those with economic privilege is not “proof” that class doesn’t matter, as some race reductionists have claimed. It’s simply affirmation that racism matters too.

Consider, for instance, my colleague Zaid Jilani’s review of comprehensive police shooting data in 2015, in which he found that 95 percent of police shootings had occurred in neighborhoods where the household income averaged below $100,000 a year. Remember that Philando Castile was pulled over, in part, because he was flagged for dozens of driving offenses described as “crimes of poverty” by local public defender Erik Sandvick. Failure to show proof of insurance, driving with a broken taillight — these are hardly patrician slip-ups. If anything is privileged, it’s the fiction that there’s no difference between the abuses suffered by wealthy black athletes and working-class blacks like Castile. Race can increase your odds of being targeted and abused. Money can help you survive abuse and secure justice — something which sadly eluded Castile.

“There is a tendency to reduce issues that have quite a bit to do with the economic opportunities available to all Americans, African-Americans among them, and in some instances overrepresented among them, to matters of race,” explained Reed, who is currently writing a book on the conservative implications of race reductionism. He pointed to the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, as well as the mass incarceration crisis, as examples. “In both those instances, Flint and the criminal justice system, whites are 40 percent, or near 40 percent, of the victims,” he said. “And that’s an awfully high number for collateral damage.” He went on: “There’s something systemic at play. But it can’t be reduced, be reducible, to race.”

About a month ago, in anticipation of writing this, I asked Twitter to remind me of any tweets or articles that had unfairly framed progressive policies as negative because they would not end bigotry. I expected maybe a dozen responses. But that thread is now at over 200 posts, and has been retweeted over 2,000 times. The scale of this is unnerving.

Sally Albright, a Democratic Party communications consultant, argues often that free college is “racist” because mostly white people go to college and it reinforces the status quo.

Senior Legal Analyst at Rewire News and popular Twitter personality Imani Gandy suggested to her 124,000 followers that caring about Wall Street is evidence of white privilege, writing: “I would love to wake up in the morning and have my first thought be ‘I hate Wall Street.’ That’s the whitest thing I’ve ever heard.”

In a similar vein, DeRay Mckesson, popular podcaster, charter school advocate, and Black Lives Matter icon, retweeted a tweet which read: “Wall Street didn’t nominate a Sec of Education that believed guns and bibles have more place in schools than LGBT and disabled students,” implying that because Wall Street isn’t to blame for anti-LGBT policies, the financial industry doesn’t merit critique from black and/or LGBT Americans at all.

When someone pointed out that New York Times columnist Charles Blow shouldn’t be uncomfortable with a 50-plus percent tax rate for rich because taxes were even higher in the New Deal era, Blow tweeted back: “You can feel free to return to the 30s. Wasn’t so great for my folks” — as though a high tax rate necessitates a return to Jim Crow terrorism.

An anonymous, but popular, Twitter personality disparaged a job guarantee program because black people “had 100% employment for 250 years,” meaning slavery, and it “didn’t help” racism.

In a Vice article, Monica Potts claims to support single-payer health care while cautioning against Sanders’s plan on the basis that it would destroy jobs worked by low-income women — never mind that it would provide those women with health care they disproportionately lack. (Her point that any job-eliminating programs would cause less harm if a strong social safety net were in place is a sound one, but it ignores that Sanders’s plan is being proposed in conjunction with exactly the types of social safety net fortifications she seeks.)

Terrell Jermaine Starr, a journalist at The Root with a history of writing articles on the theme of Sanders’s alleged black problem, wrote a begrudging acknowledgment of the senator’s new bill addressing the inequities of cash bail in a piece ungenerously titled: “Bernie Sanders Takes on Unjust Cash Bail System, but Still Doesn’t Make Direct Connection to Institutional Racism.”

Sally Albright distilled the essence of this dominant strain of criticism when she tweeted: “Sorry kids, no way around it, if you say a policy ‘helps all Americans equally,’ that policy is racist. Structural racism must be addressed.”

When Republicans pivoted to the Southern strategy in the 1960s — uniting rich and poor whites on the premise that they’d always have racial superiority — the Democrats positioned their party as a refuge for everyone else. Identity, consequently, has become centrally important to liberals. It’s not just a useful way to frame experiences which stem from broadly shared characteristics, nor is its political relevance limited to its significant organizing value. Today, identities other than white, cis, straight, and male are foundational to the Democratic Party’s understanding of itself and its ability to persist. Like the clumsy signifier “people of color,” the party defines itself via its relationship to a white male status quo. The coalition, by its very nature, depends on it.

No wonder, then, that identity has become such a lightning rod and critiques of identity politics are so polarizing.

Just look at presumed 2020 hopeful Sen. Kamala Harris’s recent defense of identity politics at the Netroots conference earlier this month.

Seeming to either misunderstand or ignore the critique of identity politics from the left, she argued that the term “identity politics” is used to “divide and it is used to distract. Its purpose is to minimize and marginalize issues that impact all of us.” “It is used to try to shut us up,” she said.

This is certainly true of the political right, which generally rejects identity politics because acknowledging its validity would require them to admit that identities are politicized in response to systemic oppression (which they deny is real), rather than a rejection of individualism.

But the left’s critique of identity politics is not really a critique of identity politics at all, but of the cynical weaponization of identity for political ends. By conflating the two, Harris managed to delegitimize the left’s critique, and strengthen the Democratic Party’s ability to continue to weaponize identity with impunity — whether or not that was her intent.

This shoring up of identity politics is not just a defense against attacks on substantive equality from the right. It’s preparation for a war against leftist candidates sure to enter the ring in 2020.Harris averred that she wouldn’t be dissuaded from talking about immigrant rights, women’s rights, equal justice, or other concerns relating to marginalized groups. Nor should she. But I suspect that this shoring up of identity politics is not just a defense against attacks on substantive equality from the right. It’s preparation for a war against leftist candidates sure to enter the ring in 2020.

The root of why some Democrats have adopted this approach feels obvious. Faced with a challenge from the left, the Democratic Party’s usual tactic of comparing itself favorably to Republicans, doesn’t work. Where the establishment offered a $12 minimum wage in 2016, Bernie Sanders argued that $15 was better. When Hillary Clinton sought to protect the ACA, Sanders said it didn’t go far enough.

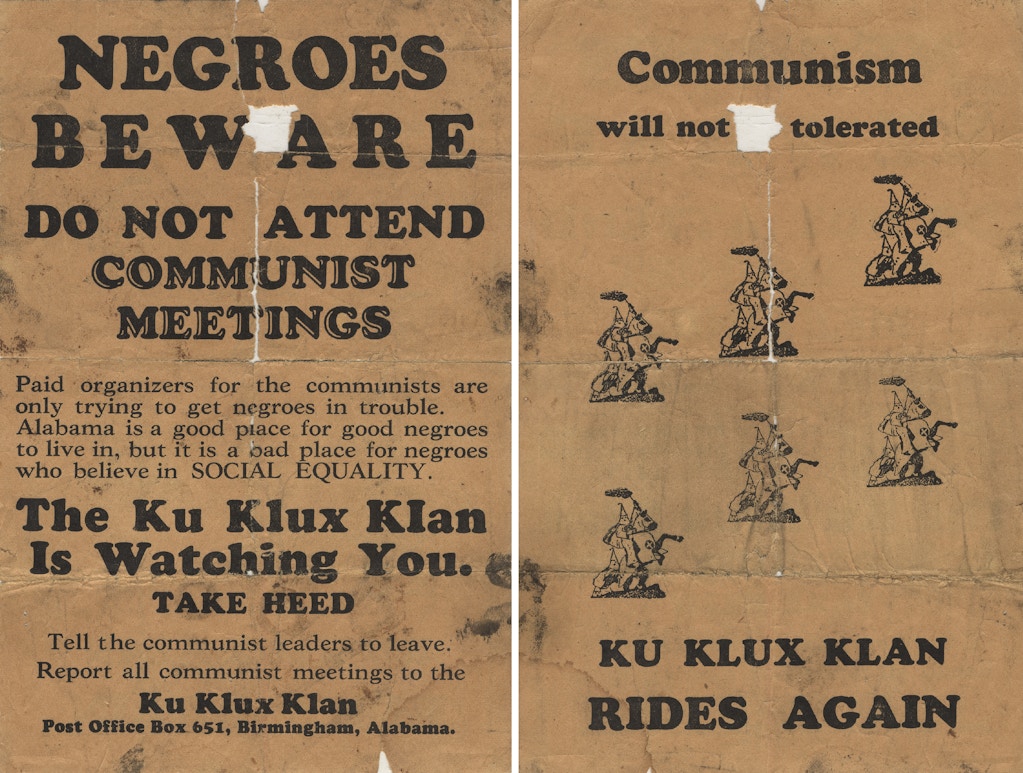

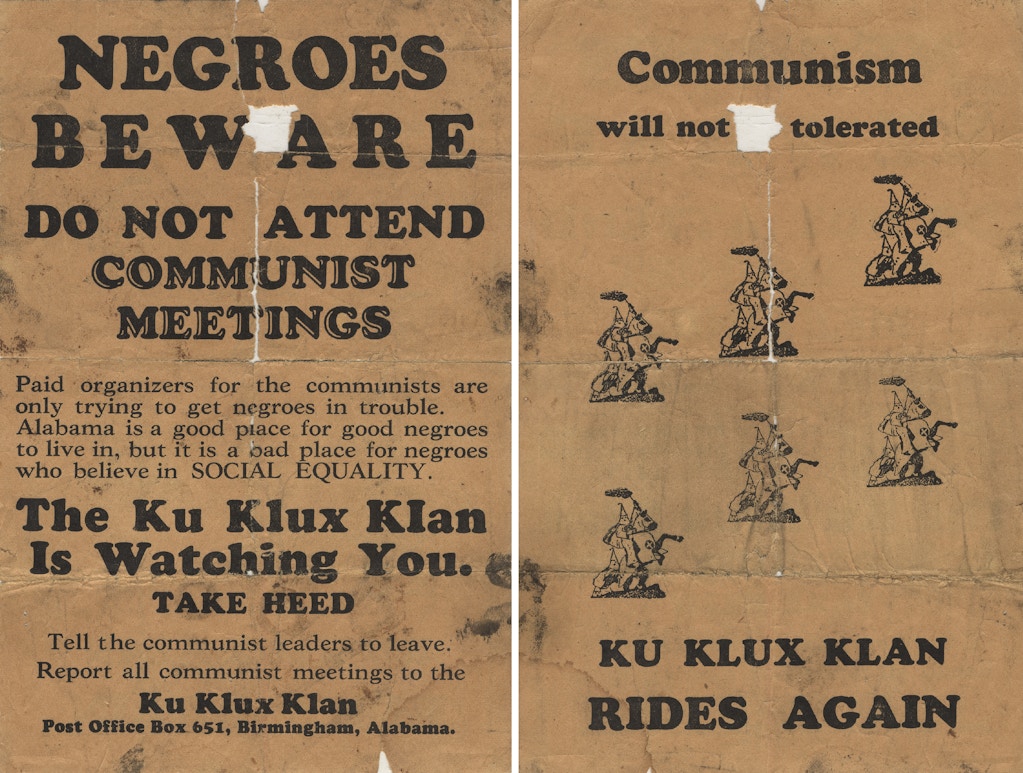

The growing popularity of left movements among black

people prompted the Ku Klux Klan to use the threat of violence to deter

blacks from communist meetings, as evidenced by this flyer from the

1930s.

Images: Alabama Department of Archives and History

In her 2017 book “What Happened,” Clinton was explicit about how frustrating she found running against Sanders to be:

Jake Sullivan, my top policy advisor, told me it reminded him of a scene from the 1998 movie There’s Something About Mary. A deranged hitchhiker says he’s come up with a brilliant plan. Instead of the famous “eight-minute abs” exercise routine, he’s going to market “seven-minute abs.” It’s the same, just quicker. Then the driver, played by Ben Stiller, says, “Well, why not six-minute abs?” That’s what it was like in policy debates with Bernie. We would propose a bold infrastructure investment plan or an ambitious new apprenticeship program for young people, and then Bernie would announce basically the same thing, but bigger.Today, most 2020 hopefuls seem to have responded to the popularity of the progressive movement by simply embracing many of its policy prescriptions. (They kind of have to: “Medicare for All” has gone from something that Clinton insisted would “never, ever” happen, to a policy which has the backing of a majority of the American public — including Republicans.)

But some still employ a mixed strategy, which pairs a shift to the left with an attack on progressivism under the pretext of anti-bigotry. This needs to end, before it ends badly.

Now, the concern that broad-based material policies will replicate, reinforce, or worsen patterns of discrimination is legitimate. It is true that in the past, “universal” programs have been distributed in an inequitable and, at times, racist manner. But that’s not a reason to forestall initiatives aimed at economic equality until some far off time at which racism is cured. Rather, it’s incentive to improve upon them.

Rhiana Gunn-Wright, the policy director for former Michigan gubernatorial candidate Dr. Abdul El-Sayed and the brains behind his comprehensive suite of policy proposals, understands this. In a recent interview, she explained that she takes an “intersectional” approach to policy — a reference to Columbia University law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw’s insight that identities intersect, overlap, and diversify the priorities of individuals within broad identity-group categories.

Gunn-Wright believes that “universal” programs are rightly criticized when they adopt a rising-tide-raises-all-ships philosophy, which can ignore or reinforce disparities across groups. But she says that policymakers can work to avoid that outcome. “The analysis of intersectionality was all about how systems are designed with either a deep inattention to all identities or attention to one identity at a time, and therefore ignoring people who lived at the intersections of those identities,” she told me. But that’s a design problem — not an argument against broad economic programs.

“I think it’s very interesting intersectionality has become such a buzzword now, and you can tell a lot of people have picked it up without ever reading the black women who created the concept,” Gunn-Wright said. “I can never imagine Kimberlé Crenshaw being like: ‘You know what? We definitely should not have single payer until we figure out race.’”

“I can never imagine Kimberlé Crenshaw being like: ‘You know what? We definitely should not have single payer until we figure out race.'”No identity should ever be sidelined. As Haney-López told me, “There’s a danger to thinking exclusively in race terms. But you kind of want to be balanced about what that danger is and how it relates to dominant political dynamics and what the resolution is, because at the same time that there’s a risk to talking about race, there’s an enormous risk to erasing it.” He’s right. But while I understand where concerns about “de-centering” race are coming from, by definition, there is no fixed “center” in intersectionality. It’s not a zero-sum game.

“We think that race, in particular, is a purely social issue and not connected to economics or reproductive justice or criminal justice,” said Gunn-Wright, arguing that, in fact, both class and race are always part of the equation. “I think identities are incredibly important and shape the way we move throughout the world, and they shape the way that people treat us and the way our government treats us. … It’s just been deployed in this way that shuts down progress instead of embracing it, and also assumes in a very strange way that black people wouldn’t want this sort of progress, or wouldn’t benefit from it.”

Touré Reed, professor of 20th century U.S. and African-American history at Illinois State University, observed that the presumption that black Americans aren’t equally or more invested in economic interventions as white Americans is “pregnant, of course, with class presumptions,” which work well for the black and Latinx professional middle class — many of whom play a significant role in defining public narratives via their work in politics or media. Since “the principal beneficiaries of universal policies would be poor and working-class people who would disproportionately be black and brown,” he told me, “dismissing such policies on the grounds that they aren’t addressing systemic racism is a sleight of hand of sorts.”

“Dismissing such policies on the grounds that they aren’t addressing systemic racism is a sleight of hand of sorts.”Intersectionality, the “buzzword” taken up so faithfully by mainstream Democrats in 2016, requires an acknowledgment that like race and sexual identity, class is a dimension that mediates one’s perspective. That means the hashtag #trustblackwomen shouldn’t collapse the interests of Oprah, a billionaire, with, well, anyone else’s. Similarly, not all blacks or Latinos should be presumed to speak equally to the interests of poor and working-class people of color. This is a truth easily internalized when Democrats consider figures like Ben Carson or Ted Cruz. It’s a more difficult reality to swallow when considering one of our own.

None of this is to say that in every scenario, race, gender, sexuality, and class are equal inputs. Affluent black athletes are still tackled by cops despite their wealth, and black Harvard professors are arrested trying to unlock their own front doors. But the fact that racism hurts even those with economic privilege is not “proof” that class doesn’t matter, as some race reductionists have claimed. It’s simply affirmation that racism matters too.

Consider, for instance, my colleague Zaid Jilani’s review of comprehensive police shooting data in 2015, in which he found that 95 percent of police shootings had occurred in neighborhoods where the household income averaged below $100,000 a year. Remember that Philando Castile was pulled over, in part, because he was flagged for dozens of driving offenses described as “crimes of poverty” by local public defender Erik Sandvick. Failure to show proof of insurance, driving with a broken taillight — these are hardly patrician slip-ups. If anything is privileged, it’s the fiction that there’s no difference between the abuses suffered by wealthy black athletes and working-class blacks like Castile. Race can increase your odds of being targeted and abused. Money can help you survive abuse and secure justice — something which sadly eluded Castile.

“There is a tendency to reduce issues that have quite a bit to do with the economic opportunities available to all Americans, African-Americans among them, and in some instances overrepresented among them, to matters of race,” explained Reed, who is currently writing a book on the conservative implications of race reductionism. He pointed to the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, as well as the mass incarceration crisis, as examples. “In both those instances, Flint and the criminal justice system, whites are 40 percent, or near 40 percent, of the victims,” he said. “And that’s an awfully high number for collateral damage.” He went on: “There’s something systemic at play. But it can’t be reduced, be reducible, to race.”

About a month ago, in anticipation of writing this, I asked Twitter to remind me of any tweets or articles that had unfairly framed progressive policies as negative because they would not end bigotry. I expected maybe a dozen responses. But that thread is now at over 200 posts, and has been retweeted over 2,000 times. The scale of this is unnerving.

Sally Albright, a Democratic Party communications consultant, argues often that free college is “racist” because mostly white people go to college and it reinforces the status quo.

Senior Legal Analyst at Rewire News and popular Twitter personality Imani Gandy suggested to her 124,000 followers that caring about Wall Street is evidence of white privilege, writing: “I would love to wake up in the morning and have my first thought be ‘I hate Wall Street.’ That’s the whitest thing I’ve ever heard.”

In a similar vein, DeRay Mckesson, popular podcaster, charter school advocate, and Black Lives Matter icon, retweeted a tweet which read: “Wall Street didn’t nominate a Sec of Education that believed guns and bibles have more place in schools than LGBT and disabled students,” implying that because Wall Street isn’t to blame for anti-LGBT policies, the financial industry doesn’t merit critique from black and/or LGBT Americans at all.

When someone pointed out that New York Times columnist Charles Blow shouldn’t be uncomfortable with a 50-plus percent tax rate for rich because taxes were even higher in the New Deal era, Blow tweeted back: “You can feel free to return to the 30s. Wasn’t so great for my folks” — as though a high tax rate necessitates a return to Jim Crow terrorism.

An anonymous, but popular, Twitter personality disparaged a job guarantee program because black people “had 100% employment for 250 years,” meaning slavery, and it “didn’t help” racism.

In a Vice article, Monica Potts claims to support single-payer health care while cautioning against Sanders’s plan on the basis that it would destroy jobs worked by low-income women — never mind that it would provide those women with health care they disproportionately lack. (Her point that any job-eliminating programs would cause less harm if a strong social safety net were in place is a sound one, but it ignores that Sanders’s plan is being proposed in conjunction with exactly the types of social safety net fortifications she seeks.)

Terrell Jermaine Starr, a journalist at The Root with a history of writing articles on the theme of Sanders’s alleged black problem, wrote a begrudging acknowledgment of the senator’s new bill addressing the inequities of cash bail in a piece ungenerously titled: “Bernie Sanders Takes on Unjust Cash Bail System, but Still Doesn’t Make Direct Connection to Institutional Racism.”

Sally Albright distilled the essence of this dominant strain of criticism when she tweeted: “Sorry kids, no way around it, if you say a policy ‘helps all Americans equally,’ that policy is racist. Structural racism must be addressed.”

Some of the worst of these

interlocutors aren’t mainstream, thank goodness, even though they have

significant influence on Twitter. The anonymous Twitter user who argued

that we have to maintain capitalism because “Ending capitalism WILL

displace people of color. Money is what keeps us in the game,” or Sally

Albright’s tweet that “Income inequality is only a priority for cis

white men,” ultimately don’t matter. But I’m concerned that the growing

popularity of this framing will make it that much easier for politicians

to exploit the left’s good faith concern about identity-based

disparities in order to disperse enthusiasm for policies that seek to

transform the economic status quo.

Ending racism is a necessary, critical goal. But that goal should be pursued in tandem with efforts to address the effects of racism. The wage gap, the health care gap, the education gap, the debt gap — all these disparities would be narrowed by progressive, intersectional economic programs. As popular opinion coalesces around these policies, it’s crucial that we not let our best impulses be weaponized against our interests, any more than conservatives weaponize the worst impulses of their constituents against theirs.

Ending racism is a necessary, critical goal. But that goal should be pursued in tandem with efforts to address the effects of racism. The wage gap, the health care gap, the education gap, the debt gap — all these disparities would be narrowed by progressive, intersectional economic programs. As popular opinion coalesces around these policies, it’s crucial that we not let our best impulses be weaponized against our interests, any more than conservatives weaponize the worst impulses of their constituents against theirs.

No comments:

Post a Comment