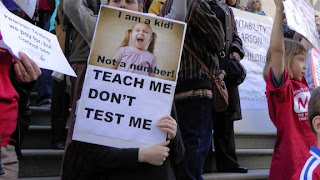

A 2012 rally held by

United Opt Out (Licensed through Creative Commons (Courtesy of

Flickr user Chalkface, CC BY-SA 2.0)

At a

September 16 PTA meeting, Castle Bridge

elementary school parents received some unwelcome news:

the

New York City Department of Education was dropping new

standardized tests on their children in kindergarten through

second grade. Kindergarteners would take a break from learning

the alphabet to bubble A through D on

multiple-choice exams. Images

next to each problem—a tree, a mug, a hand—would serve as

signposts for students still fuzzy on numbers.

The district purchased

the tests to meet

the

state's new teacher evaluation laws. In elementary schools

that don’t serve grades three through eight, No Child Left

Behind testing dictates don’t apply, necessitating a

supplemental test.

Castle Bridge, a progressive K-2

public school in Washington Heights, is among 36 early

elementary schools in

the New York City targeted for

the new

assessments.

According to Castle Bridge mom Dao Tran, those at

the PTA meeting were appalled. This was the first they’d heard

of the tests. Talk of refusal arose among some parents, but

they knew that “acting as individuals wouldn’t keep testing

culture from invading our school.” They opted for collective

action.

Starting in early October, a core group organized

meetings, disseminated fact-sheets on standardized testing and

galvanized a spirited conversation at the next PTA meeting.

Parents shared their concerns, weighing the risks of refusal.

At one meeting a parent whose first language was Spanish

testified to the pain and anxiety brought on by taking

standardized tests in his youth.

Within three weeks,

80 percent of parents had submitted in

writing their intention to opt out of

the new tests. Principal

Julie Zuckerman put her weight behind

the families, agreeing,

according to Tran, that “these tests would be

the wrong thing

to do.”

In a statement, parents wrote, “The K-2

high-stakes tests take excessive testing to its extreme:

testing children as young as four serves no meaningful

educative purpose and is developmentally destructive.”

By October 28, families of 93 of the 97 students

subject to the tests had opted out. The near-unanimous boycott

is unprecedented in the city.

It also signals the first stirrings of a growing

test-resistance movement poised to reach new heights this

academic year.

---

“Who do you like more: A, Mommy; B, Daddy; or C,

Frederick Douglas?”

When eight year-old Jackson Zavala posed this

multiple-choice query to his baby sister, his mother Diana

Zavala knew something was amiss.

Jackson, a student with special needs in

communications, had been a “curious, interested” student until

third grade, the first year NCLB-mandated state tests take

effect. It was then his mother noticed that he “became anxious

and bored by school.” She saw that his homework had become

rote and repetitive, his class time devoted more to test prep,

and his speech inflected with the language of multiple choice

testing.

In time Zavala decided that the influence of

testing in class had led to “damage to his personal well-being

and originality” and “a strangling of his curriculum.”

She poked around and found a New York City-based

test resistance group called Change the Stakes. With the

group’s support, opting-out was a less fraught decision. “We

had a family, a connection with a community of people” also

resisting the test.

For the last two years, Jackson has refused state

exams.

But actions like Zavala’s have been sporadic in

recent years. It wasn't until this past spring that the

testing opt-out movement had its first bumper crop.

In January, high school teacher and activist

Jesse Hagopian helped lead

the dramatic test boycott at Seattle’s Garfield

High School. Teachers refused to administer, and students

refused to take

the state test, which organizers argued wasn’t

aligned to curriculum and provided statistically unreliable

results. After a months-long standoff with

the district which

saw teachers

threatened with suspension,

the

district relented and allowed

the high school to forgo

the

test.

Since spring, Hagopian has been traveling

the

country speaking at events and advising schools “who want to

replicate”

the success of Garfield’s boycott. He even took

part in a panel at NBC’s

Education Nation in early October to

rail against “

the inundation of our classrooms with

standardized testing.”

But while Seattle attracted

the lion’s share of

national media attention, schools throughout

the country saw

increasing numbers of students refuse standardized tests.

Denver,

Chicago,

Portland,

Providence and

elsewhere wi

tnessed opt-outs

large and small.

Parent groups in Texas succeeded in

halving the number of

standardized tests given there. Students donned fake gore for

“zombie crawls” in

two cities, highlighting

the

deadening effects of test-mania. Little ones participated in a

“

play-in” at district offices in

Chicago, living

the motto that tots “should be blowing

bubbles, not filling them in.”

This activism comes as a reaction to the growth

of a testing apparatus unmatched in US history. Bipartisan No

Child Left Behind legislation in 2002 laid the groundwork,

requiring states to develop assessments for all students in

grades 3-8, and threatening schools that fall short of yearly

benchmarks. The Obama Administration's Race to the Top

heightened the stakes, encouraging states to develop

test-based teacher evaluations and adopt Common Core

standards.

Together they aim to capture all

the complexities

of a student’s learning in a few digits that sometimes add up

to schools closed and teachers fired. Meanwhile

three quarters of districts facing

NCLB sanctions have reported cutting

the time allotted to

non-tested subjects like science and music. And since Race to

the Top’s passage in 2009, about

two thirds of states have ramped

up their teacher evaluation systems, with 38 now explicitly

requiring evaluations to include test scores.

As standardized testing has grown, so too has its

shadow. In 2011,

the United

Opt Out movement was established to counter

the

pro-testing mania sweeping

the country. Its website provides

opt-out

guides for 49 states and

the

District of Columbia, and connects a burgeoning community of

grumbling and disaffected parents.

“I didn’t ask for high-stakes testing,” says Tim

Slekar, United Opt Out’s founder. Slekar sees participating in

a large-scale opt-out movement as a way for him and his

children to “reclaim public education.”

United Opt Out currently claims six thousand

members, but Slekar says its ranks are ballooning. “I’ve

spoken to more parents in the last three weeks than in the

past three years.”

In New York,

dozens of grassroots

organizations have emerged to address testing. Parent

advocates recently formed New York State Allies for Public

Education (

NYSAPE)

to serve as an umbrella group.

The organization draws together

parents from big cities and sleepy byways, united in “seeing

the damage to

the kids,” says NYSAPE co-founder Chris Cerrone.

In

the tiny West New York district where

Cerrone’s children go to school,

the number of students opting

out

rose sixfold between 2012 and 2013.

At Springville Middle School, enough students boycotted to

trigger NCLB’s Adequate Yearly Progress alarms.

NYSAPE has scrutinized state opt-out procedures

and found New York has no provision for addressing student

test refusal. The knowledge that students can forgo tests

without individual repercussions has emboldened parents across

the state.

In schools from

Long Island to

Albany, from

the Adirondacks to

Lower Manhattan, students pushed

their pencils aside and refused state tests this past spring.

It was a high water mark for

the opt-out movement in New York,

but still totaled less than

one percent of students.

The question remains as to whether boycotts that

exceed 5 percent of a school’s population, and thus preclude

schools from making Adequate Yearly Progress, can invite

consequences.

National testing advocacy group

Fairtest treads cautiously

here.

Chris Cerrone calls it “a myth,” however,

pointing to the fact that despite increasing opt outs, no

school in New York has lost funding due to student test

refusal. But it's still unclear.

---

On October 27, eight days after

the Castle Bridge

boycott went public,

the Chief Academic Officer of New York

City schools

told a state Senate committee that

the K-2 bubble

tests

the city had selected in August were “developmentally

inappropriate.” He indicated that

the city would move towards

“performance assessments” in these grades, noting that

the new

state teacher evaluation law mandates some form of assessment

in these grades.

It’s the latest in a series of conciliatory

gestures by the Department of Education toward parents and

educators who’ve been raising hackles for years.

Some of

the most aggressive pushing on testing

recently comes from grassroots anti-testing group

Change

the Stakes. Incited by

the perceived onslaught of

Common Core-aligned state tests,

the group published

sample opt-out letters and rallied parents at

numerous schools in support of a boycott.

This knowledge is empowering. Parents at Castle

Bridge delighted at the realization that they could yank their

kids from tests. Don Lash, parent of a Castle Bridge

first-grader, said “just being aware there was an alternative”

was a revelation.

Similar resistance efforts are underway at Earth

School, a K-5 elementary in the same progressive network as

Castle Bridge, where 51 students opted out last year. Special

education teacher and parent Jia Lee played a central role in

organizing last spring’s boycott, which included her

fifth-grade son. Though many teachers will only whisper their

support with opt-out parents, Lee is unafraid to speak

publicly.

As a teacher, Lee wearied of the third-party

test-prep materials flowing into schools. “You don’t need

packaged curriculum to have meaningful learning,” she says. As

a parent and CTS member, she feels “the only way to stop this

is to deny the data.”

And in her advocacy, Lee sees the movement in the

city metastasizing. “Schools that weren’t talking about this

last year are starting to talk,” she says.

Parents at Castle Bridge likely won’t be backing

down. Says Castle Bridge parent Vera Moore, “I will oppose

testing as long as I am able.”

Interestingly, Shael Polakow-Suranksy, New York’s

Chief Academic Officer, isn’t drawing any red lines on test

refusal. Regarding Castle Bridge, he said there would be “no

consequences.” And children who opt out of state exams can

still advance to the next grade, so long as they submit

alternative portfolios, as per district policy. On the

possibility of future boycotts, Polakow-Suransky won’t

speculate. The recent boycott had little or no effect on his

decision to renounce bubble tests for toddlers. “Preceding the

news of the boycott we were exploring other options,” he says.

But it’s not just K-2 tests that parents are

resisting. The opt-out movement reflects the inevitable

response of citizens when dramatic changes are imposed

unilaterally on democratic institutions. Unable to influence

the content of curricula or nature of assessments through

democratic means, direct resistance becomes perhaps the only

option.

Diana Zavala says parents are taking the reins of

school governance, but with one key difference from

administrators: “You can’t fire us.”