Feeding the schoolkids was a

tactical masterstroke (as doing the right thing so often is)...

“What are their demands?” — that the teachers are

making, as opposed to the demands that careless journalists say they are

making; and then I’ll present a grab bag of interesting characteristics

worth noting, partly about West Virginia, partly about this strike.

I’ll conclude with some remarks on the role of the Democrat Party in

creating the conditions that led to the strike....

we enter phase three! The rank and

file rejected the deal, turning the strike into a wildcat strike. ..... by Lambert Strether

If you continue reading Ed Notes you will learn everything there is to share about teacher actions in W. Virginia and Oklahoma - and hopefully other places too until you can't take anymore.

For the 2nd West Virginia strike article of the day that I'm posting, this one looks like a goodie even though it was posted over a week ago. Look at the opening line up top. Feeding the kids. I can just imagine some of the selfish oafs who comment on mine and other blogs thinking, "how social justicy" - why worry about the kids?

I still have at least one more to post later around midnight. (I want to give readers a chance to get to the articles.) Why am I focusing on WV and OK -- lessons galore -- and not only what you may be hearing from the left the center or the right. By reading everything we can come up with some conclusions - hopefully - on how we may be affected here in NYC and beyond. The answer may very well be not at all.

Note the section in red with the * - these 3 unions have not gotten along and according to a West V teacher I spoke to, there is still a lot of tension and resistance to working together from union leaders at the top --- yes, this crap never goes away.

I still have to report on the March 10 Saturday night event attended by 300 people who heard directly from 3 WV teachers.

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2018/03/notes-west-virginia-teachers-strike-2018.html#comment-2933610

By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Obviously, the West Virgina teachers strike is a big story, and

potentially an enormous one, especially if it turns out to be the more

successful cousin of the

the Wisconsin State Capitol occupations of 2011 which followed

Tahrir Square and preceded

Occupy proper.

(As we’ll see below, “teachers strike” is a bit of a misnomer, and

that’s important, but I think we’re stuck with the phrase.) So I ought

to present a general theory, or at least a hot take, but on working

through the sources as best I could, I realized how little I knew of

realities on the ground[1], so my ambitions for this post will be more

modest. First, I’ll review the state of play; then, I’ll reinforce the

demands — one of the nice things about a strike is that there is an

answer

to the question “What are their demands?” — that the teachers are

making, as opposed to the demands that careless journalists say they are

making; and then I’ll present a grab bag of interesting characteristics

worth noting, partly about West Virginia, partly about this strike.

I’ll conclude with some remarks on the role of the Democrat Party in

creating the conditions that led to the strike.

First, one piece of background. There was a massive and successful eleven-day West Virginia teachers strike in 1990.

The Charleston Gazette-Mail:

In March 1990, teachers across West Virginia refused to go to work

and headed to the picket line, shutting down hundreds of schools for 11

days. They walked out after legislative leaders and Gov. Gaston Caperton

were unable to come to an agreement on a package of pay raises.

The 1990 strike is often referred to as West Virginia’s first

statewide teacher strike, but eight of the state’s 55 counties didn’t

participate in the walkout.

Teachers returned to work after union leaders secured promises from

state Senate President Keith Burdette and House Speaker Chuck Chambers

to address teacher pay and other issues.

Among other results of the strike, teachers received a $5,000 pay

increase, phased in over three years. That boosted West Virginia

teachers’ salaries from 49th in the nation before the strike to 34th

after the raises were implemented. Teachers also got new support and

training programs, and money was set aside for faculty senate groups in

every school, in an effort to give teachers more of a voice in education

policy decisions.

Then as now, the strike was “unlawful” without being “illegal” (

I’m not sure I understand that, either)

but in any case nobody was arrested (even though, unbelievably,

teachers have no right to collective bargaining in West Virginia, and

their wages are set by the legislature). Two other differences leap out:

In 2018, all 55 counties participated (the hash tag is

#55strong), and this time, the rank and file rejected the “secured promises” obtained from the Governor by the union leadership.

The State Of Play

So far, the strike has gone through three phases: The build-up, the

walkout, and the wildcat strike. Let’s look at each phase in turn.

Labor Notes has a good retrospective

of the thinking and organizing during the build-up to the strike, sadly

(or fortunately?) not made visible to the rest of the world by the

press:

The first rumblings began late last year, when a group of teachers

formed a secret Facebook page[2] and started planning a “lobby day” at

the state capital on Martin Luther King Day, when they knew the

legislature would be in session. Word spread, and soon the West Virginia

Education Association, the state’s NEA affiliate, was planning an

official rally.

“This was almost completely a grassroots movement,” said Erica

Newsome, an English teacher in Logan County. “The unions kind of

followed us.”

Organizers estimate 150 people showed up. “The rally was kind of

small,” said Ashlea Bassham, a teacher at Chapmanville Regional High

School, “but then it just sort of happened.”

Teachers and school service employees started holding walkout votes

county by county. West Virginia has two statewide teachers unions,

affiliates of the AFT and NEA, which often compete for membership. There

is also the West Virginia School Service Professional Association, or

WVSSPA,* which represents bus drivers, cafeteria workers, custodians, and

clerical workers. But teachers and school service employees decided

that in this case, any school employee could vote—whether they were a

member of any one of the unions or no union at all.

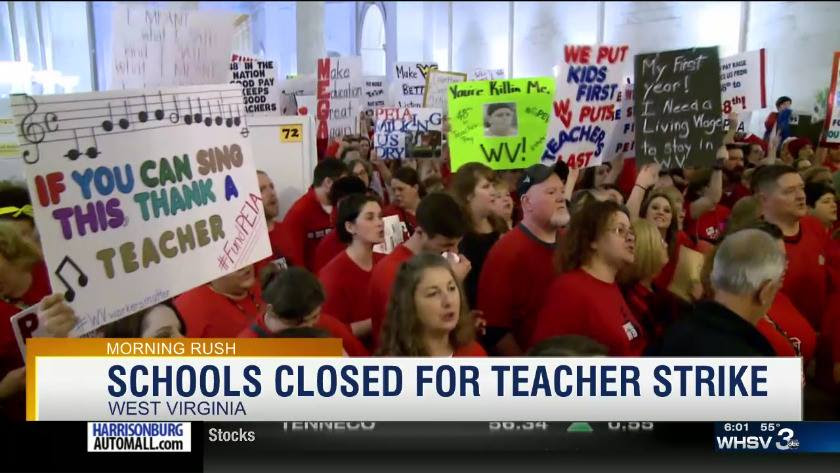

We now enter the walkout phase, marked by Capitol protests and rallies:

Strikers converged on the capital again. This time there were 1,000

teachers, public employees, students, and parents at the statehouse.

“The gallery filled up too quick for me and some co-workers to go

in,” said Bassham, “So we waited in the breezeway to talk to our state

legislators. Some of our representatives were willing to talk and take a

minute and listen, and some of them had their heads down, walking

really quickly.”

The legislature responded by announcing a temporary freeze to Public

Employees Insurance Agency (PEIA) premium increases, and offered a two

percent pay raise in the first year.

At this point (February 27), the union leadership declared victory[3].

The Payday Report:

After 4 days of striking, the West Virginia teachers’ union has reached an agreement to end their historic work stoppage.

Under the deal, the teachers would get a 5% raise during the first year. Initially, teachers had been offered 1% raise.

The state also agreed to appoint a task force to look into improving

the troubled Public Employee Insurance Agency [PEIA], which insures the

teachers.

The teachers will return to classes on Thursday after a brief cooling-off period.

In fact, that didn’t happen, and we enter phase three!

The rank and

file rejected the deal, turning the strike into a wildcat strike. Jacobin interviewed Jay O’Neal, a middle-school teacher and union activist in Charleston:

[O’NEAL]: As is the case these days, everybody was on their phones,

trying to follow the news to get a sense of what was going on.

Within ten minutes, we found out through the governor’s press

conference [not a good look!] that a deal had been reached. Teachers and

school staff would get a 5 percent pay raise, and 3 percent for all

state employees. The governor also said that a task force would be set

up to figure out how to improve PEIA, our statewide health insurance

plan for public sector workers.

Fifteen minutes after the press conference, union leaders came out

and addressed the crowd. The basic problem was that they presented this

deal as a victory. They told us we’d be out on strike one more day, then

return to school on Thursday.

People were up in arms, really frustrated. Of course, a 5 percent

raise is great, but what we’ve been really fighting for in this struggle

is PEIA. This has been a huge issue, causing problems for years.

They’ve been cutting our health insurance over and over, making it

really expensive to survive.

So when it was announced that all we got on PEIA was a task force, people were upset.

And:

In my county at least, the sentiment is that

we’re not going back to work until there’s solid proof that our demands are going to be met. Our biggest fear is that they’re just going to keep pushing back the question of PEIA.

(There was also a hilarious subplot where Governor Justice pulled

“$58 million out of thin air”

to pay for the raises, IIRC continuing a storied tradition in the

state.) And in fact, the rank and file were right on the money, as

hilarity ensues in the state legislature. The

Charleston Gazette and Mail:

On Saturday evening, the Senate Finance Committee took up a pay raise

bill passed by the House, and reduced the pay increase for teachers,

school service workers and State Police troopers from 5 percent to 4

percent.

But the Senate then, mistakenly, passed the House version of the bill

with the 5 percent raise, rather than the 4 percent version. After

Senate leaders announced the mistake, senators walked back their passage

vote and certain procedural votes, and passed the bill with a 4 percent

raise after 9:30 p.m. Saturday.

House members wouldn’t agree to that change, and both sides appointed

three members to a conference committee, which will try to hash out the

differences on the bill.

“At this point, the three organizations announce that we are out

indefinitely — we will not accept the 4 percent,” said Dale Lee,

president of the West Virginia Education Association, speaking on behalf

of his group, as well as the state arm of the American Federation of

Teachers and the West Virginia School Service and Personnel Association,

following Saturday’s committee vote. “Until this bill passes at 5

percent, we will be out indefinitely.”

Immediately after the committee amendment vote (the first time around), jeering broke out from the Senate gallery.

(Whether the Senate leadership was incompetent, or engaged in crude delaying tactics I cannot say.)

The Conference Committee might meet Sunday, but

the Senate reconvenes Monday at 11AM. So that is where we are.

What Are Their Demands?

All I’m going to do here is contrast the lazier headlines with what the striking teachers are saying. The headlines:

But as we have already seen,

health insurance (PEIA) was a key issue[4], besides the raise; that’s what teacher Jay O’Neal says above, that’s what teacher Katie Endicott

told the New York Times, that’s what teacher Samantha Nelson

told CNN, and that’s what

the Charleston Gazette and Mail found in its reporting:

Many school employees interviewed say maintaining Public

Employees Insurance Agency health insurance costs and benefits at their

current levels is a bigger issue than pay increases. PEIA Finance Board

members, at the governor’s urging, have delayed premium increases and

benefit cuts, but teachers say that just delays the pain, and a

long-term solution is needed.

That’s also what

the Los Angeles Times found:

At the heart of the matter, teachers say, isn’t their salaries. It’s their soaring healthcare costs.

“We’ve seen [people say] ‘teachers are not happy with the 5%

increase’ — that’s not it at all,” said Mary Clark, 49, a fifth-grade

teacher in Monongalia County. “That’s not what kept us out. It’s the

insurance. That’s the big deal.”

In West Virginia, teachers and other state employees receive health coverage through the Public Employees Insurance Agency.

The state program is funded 80% by employers and 20% by employees.

That means as healthcare costs continue to rise significantly, the

program’s long-term solvency requires “significant revenue increases in

employer and employee premiums” over the next five years, according to

an October 2017 financial report prepared for PEIA.

In other words, employees are going to need to pay up. “They are wanting to raise our rates,” Clark said.

But there’s a problem with that: After teaching for a little more

than 10 years, “I’ve not seen [my take-home pay] go up any at all,” not

even counting inflation, Clark said. If her healthcare costs increase,

“that’s not feasible.”

Which is obvious when you think about it: What’s the point of a raise

if your insurance company takes the money right out of your pocket,

like you’re some sort of pass-through?

Bottom line here is to

beware of any source that presents the raise

(4% vs 5%) as the only, or even the main issue. That includes, as we

have seen, much of the press, but also the Governor and the legislature,

and the union leadership (at least as far as I can find). PEIA needs to

be fixed, and not by some pissant kick-the-can-down-the-road [family

blogging] commission, either.

West Virginia on the Ground

Now the promised grab bag: Items I noticed collecting information for

this story that seem to be unique to West Virginia. The first two

relate to the history and culture of the state; the final three are

about this strike in particular.

Item one: The word “county.” Teacher O’Neal uses it in his interview above:

From below,

I can only really speak about the situation in my county,

which is local to Charleston. We decided to have a meeting at 1 PM to

try to straighten things out and to get some correct information. It was

all super last minute, we had to plan it in a couple of hours. We met

in a nearby church. The room was absolutely packed, with pews and aisles

filled way past capacity.

And I ran across teachers talking about their counties constantly.

Now, I don’t know what to make of this. I am very much from my place or

patch in Maine, but I situate myself more in my town, or at the

intersection of the Penobscot and the Stillwater Rivers; I don’t think

myself as being from Penobscot County at all. Perhaps some West Virginia

readers can enlighten us?

Item two: West Virgina has a storied labor history. State Senator Richard Ojeda, a Democrat, amazingly enough, in

the Morgan County, USA blog:

“The teachers of West Virginia are not just fighting for themselves,

our children or all public employees,” Ojeda wrote. “In my view,

teachers in West Virginia are joining a fight for the soul and spirit of

West Virginia that started hundreds of years ago.”

“Hundreds of years ago, investors came to West Virginia and purchased

most of the land for all but nothing. Even today, you will be hard

pressed to find many people in West Virginia who own their mineral

rights.”

“They wanted our salt, timber and coal. They came in, paid our people

essentially nothing for it and then put in the railroad. West Virginia

has always been a colony.”

I’ll stop there, but it’s worth a read in full. (It’s is a rolled up

Tweet storm from Ojeda, but I wanted to give a local site some hits.)

Item three, now on the strike itself: Feeding the schoolkids was a

tactical masterstroke (as doing the right thing so often is). From

Today:

During the four-day strike, teachers throughout West

Virginia went out of their way to provide students with food. Teachers

and staff at Horace Mann Middle School in Charleston prepared bagged

lunches to send home with their students before they hit the picket

line. Others worked with local food pantries to drop food off at

students’ homes.

Item four:

All school unions are involved, not just the teachers, unlike the 1990 strike[6] (making the phrase “teachers strike” a misnomer).

The Charleston Gazette Mail:

Teachers, this time joined by school service personnel,

walked off the job Thursday…. The 1990 strike also did not involve

public school service personnel, a category that generally includes

non-teachers, like bus drivers and cooks.

This is a second tactical masterstroke (besides, again, being the

right thing to do). Awkward situations described in this photo caption

are avoided:

Protesters block school buses from leaving a garage during the West Virginia teachers’ strike on March 9, 1990.

This time, the bus drivers walked out with the teachers (which certainly does make it easier to enforce the school closures).

Item five: The teachers (and cooks and bus drivers and janitors and

all school employers) are, as Ojeda points out, fighting for

all West Virginia public employees, not just themselves, since PEIA stands for “ Public Employee Insurance Agency.” A third tactical masterstroke (and again, the right thing to do).

Actually, having written the items, I now see a common thread between them, or at least for two through five: Solidarity.

Conclusion

“West Virginia Spring” may

be over-stating the case[5], but the teachers strike — need a better

phrase! — is already an interesting and potentially important flashpoint

(especially if the teachers in

Oklahoma follow their lead,

or even Florida, if Florida teachers decide they don’t want to be

security guards on top of everything else). Before I close, I did

promise I’d have a word to say about the role of the Democrat Party in

all this.

First, Governor Justice is a piece of work.

Vice:

The towering Justice, who owns coal companies, resorts,

and a host of other businesses, has emerged as the bete noire of the

saga. He won his office running a Trump-like campaign as an outsider businessman, but

flipped from Democrat to Republican at a Trump rally in Huntington last summer. As West Virginia’s only

billionaire, Justice has developed a reputation for not paying taxes or federal fines—a fact frequently touted on signs and in conversations among the teachers striking for better pay.

Governor Justice, in other words, besides being self-funded, is a

Blue Dog with the courage of his (Republican) convictions (rare, I

know). He is, that is, exactly the sort of candidate that

the DCCC is trying to foist on us to make sure, among other things, that #MedicareForAll “never, ever comes to pass.”

Second, West Virginia troubles with PEIA are due to tax policies

suppported by both parties, very much including a second Blue Dog, Joe

Manchin.

HuffPo:

A decade ago, West Virginia began gradually winding down certain

business taxes that could have helped pay for the across-the-board

raises that teachers haven’t seen in four years. They also could have

helped fill the funding shortfall in the Public Employee Insurance

Agency, or PEIA, which many workers list as their top concern.

Although Republicans now control both chambers of the statehouse, the

tax cuts that Over the following years, the state wound down its

corporate net income tax rate from 9 to 6.5 percent, and phased out its

business franchise tax. It also slashed its tax on groceries from six to

three percent, and later did away with it entirely under Manchin’s

successor, Democrat Earl Ray Tomblin. Over the same span, the state also

created a family tax credit, increased its homestead exemption and got

rid of an alternative minimum tax and corporate charter tax, according

to the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy.

All told, those cuts diminished state revenue by more than $425

million each year, the center estimates.squeezed the state budget were a

bipartisan undertaking. Then-Gov. Joe Manchin, a Democrat who’s now one

of the state’s two senators in Washington, had urged legislators to

pursue the tax cuts in 2006, arguing that West Virginia needed to slash

taxes on corporations in order to be competitive with other states.

(Of course, the best way to fix PEIA would be to remove health insurance from its remit entirely by passing #MedicareForAll.

Manchin, naturally, does not support that.)

I’ll close with Th

e New Yorker’s perspective:

“Appalachia was not different from the rest of America,”

the Appalachian historian Ronald Eller wrote ten years ago, in his

history of the region, “Uneven Ground.” “It was in fact a mirror of what

the nation was becoming.” Maybe that is the real source of the

suspense, in the conflict between educators wearing red and the

Trump-supporting governor: it isn’t at all obvious whether these

teachers are professionals in a middle-class place or workers whose

footsteps get tracked by an app[7], because it isn’t at all obvious what

the nation is becoming.

Well….

NOTES

[1] Whinging a bit: Google News gets worse and worse, so it’s hard to

find stuff; newsrooms are being slashed, which means there’s less to

find;

the labor beat,

at least in the newsroom, is a thing of the past; and social media

nuked a lot of the small blogs (and Facebook search is miserably

inadequate, even if it weren’t so toxic I can’t bring myself to use it

anymore). All of which is by way of asking readers, especially West

Virginia readers, for local sources I should be looking at. Surely there

are some small West Virginia political blogs worth reading?

[2] Not, of course, “secret” to

Facebook. Gawd knows who Facebook was selling that data to.

[3] See this clickbait tear-jerker from CNN: “

This 6th-grader helped end West Virginia teachers’ strike.” Always “this.” Never “these.”

[4] Stoller comments:

[5] Although it’s worth noting that the Quebec

printemps érable — a really horrible pun, think about it —

student strike was also in the education sector.

[6] “Higher” education should take this to heart, I think.

[7] This is a reference not only to

Amazon warehouse workers, but to West Virginia teachers.

Katie Endicott:

“They implemented Go365, which is an app that I’m supposed to download

on my phone, to track my steps, to earn points through this app. If I

don’t earn enough points, and if I choose not to use the app, then I’m

penalized $500 at the end of the year.”

![[Photo: A large crowd of teachers gather ouside of West Virginia's state capitol during the teachers strike.]](https://rewire.news/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Strike-1-740x525.png)