Michael Fiorillo sent this follow-up piece on the poor white working class.

from the American Conservative. Michael who is left gets credit for his wide-ranging reading. Vance grew up poor white and ended up at Yale law school after serving in the marines. This is the follow-up interview where so many interesting points about both white and black poor are made. The Trump appeal he points out while including elements of racism, not in the least bit inspired by the fact that the white poor are often totally ignored, also touches on some things that resonate. Like the arrogance and condescension of liberals and people on the left. I actually saw an example of that at the MORE retreat yesterday. And this article reminds me of Mike Schirtzer who entered MORE 4 years ago with a white working class mentality and how some people rolled their eyes. Mike has gotten to see a lot of angles he was not aware of before but he also has maintained his gut level white working class instincts. While I never viewed myself as coming from white working class roots - both my parents were ILGWU garment workers - but Jews never seem to feel they would get stuck and not be able to rise out like the despair described in these articles.

An interesting thought on my part: Is it ever possible to unite the black and white poor? Maybe an FDR type but we always seem to need a massive crisis. Obama looked to be a possibility but as a neo-liberal and also being black made that impossible. He talked FDR but was more Regan.

Trump: Tribune Of Poor White People

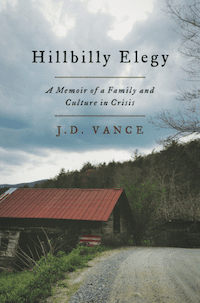

I wrote last week about the new nonfiction book Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and a Culture in Crisis

by J.D. Vance, the Yale Law School graduate who grew up in the poverty

and chaos of an Appalachian clan. The book is an American classic, an

extraordinary testimony to the brokenness of the white working class,

but also its strengths. It’s one of the best books I’ve ever read. With

the possible exception of Yuval Levin’s The Fractured Republic, for Americans who care about politics and the future of our country, Hillbilly Elegy

is the most important book of 2016. You cannot understand what’s

happening now without first reading J.D. Vance. His book does for poor

white people what Ta-Nehisi Coates’s book did for poor black people:

give them voice and presence in the public square.

This interview I just did with Vance in two parts (the final question I asked after Trump’s convention speech) shows why.

RD: A friend who moved to West Virginia a couple of years ago

tells me that she’s never seen poverty and hopelessness like what’s

common there. And she says you can drive through the poorest parts of

the state, and see nothing but TRUMP signs. Reading “Hillbilly Elegy”

tells me why. Explain it to people who haven’t yet read your book.

J.D. VANCE: The simple

answer is that these people–my people–are really struggling, and there

hasn’t been a single political candidate who speaks to those struggles

in a long time. Donald Trump at least tries.

What many don’t understand is how truly

desperate these places are, and we’re not talking about small enclaves

or a few towns–we’re talking about multiple states where a significant

chunk of the white working class struggles to get by. Heroin addiction

is rampant. In my medium-sized Ohio county last year, deaths from drug

addiction outnumbered deaths from natural causes. The average kid will

live in multiple homes over the course of her life, experience a

constant cycle of growing close to a “stepdad” only to see him walk out

on the family, know multiple drug users personally, maybe live in a

foster home for a bit (or at least in the home of an unofficial foster

like an aunt or grandparent), watch friends and family get arrested, and

on and on. And on top of that is the economic struggle, from the

factories shuttering their doors to the Main Streets with nothing but

cash-for-gold stores and pawn shops.

The two political parties have offered

essentially nothing to these people for a few decades. From the Left,

they get some smug condescension, an exasperation that the white working

class votes against their economic interests because of social issues, a

la Thomas Frank (more on that below). Maybe they get a few handouts,

but many don’t want handouts to begin with.

From the Right, they’ve gotten the basic

Republican policy platform of tax cuts, free trade, deregulation, and

paeans to the noble businessman and economic growth. Whatever the

merits of better tax policy and growth (and I believe there are many),

the simple fact is that these policies have done little to address a

very real social crisis. More importantly, these policies are

culturally tone deaf: nobody from southern Ohio wants to hear about the

nobility of the factory owner who just fired their brother.

Trump’s candidacy is music to their

ears. He criticizes the factories shipping jobs overseas. His

apocalyptic tone matches their lived experiences on the ground. He

seems to love to annoy the elites, which is something a lot of people

wish they could do but can’t because they lack a platform.

The last point I’ll make about Trump is

this: these people, his voters, are proud. A big chunk of the white

working class has deep roots in Appalachia, and the Scots-Irish honor

culture is alive and well. We were taught to raise our fists to anyone

who insulted our mother. I probably got in a half dozen fights when I

was six years old. Unsurprisingly, southern, rural whites enlist in the

military at a disproportionate rate. Can you imagine the humiliation

these people feel at the successive failures of Bush/Obama foreign

policy? My military service is the thing I’m most proud of, but when I

think of everything happening in the Middle East, I can’t help but tell

myself: I wish we would have achieved some sort of lasting victory. No

one touched that subject before Trump, especially not in the Republican

Party.

I’m not a hillbilly, nor do I descend

from hillbilly stock, strictly speaking. But I do come from poor rural

white people in the South. I have spent most of my life and career

living among professional class urbanite, most of them on the East

Coast, and the barely-banked contempt they — the professional-class

whites, I mean — have for poor white people is visceral, and obvious to

me. Yet it is invisible to them. Why is that? And what does it have to

do with our politics today?

I know exactly what you mean. My grandma

(Mamaw) recognized this instinctively. She said that most people were

probably prejudiced, but they had to be secretive about it.

“We”–meaning hillbillies–“are the only group of people you don’t have

to be ashamed to look down upon.” During my final year at Yale Law, I

took a small class with a professor I really admired (and still do). I

was the only veteran in the class, and when this came up somehow in

conversation, a young woman looked at me and said, “I can’t believe you

were in the Marines. You just seem so nice. I thought that people in

the military had to act a certain way.” It was incredibly insulting,

and it was my first real introduction to the idea that this institution

that was so important among my neighbors was looked down upon in such a

personal way. To this lady, to be in the military meant that you had to

be some sort of barbarian. I bit my tongue, but it’s one of those

comments I’ll never forget.

The “why” is really difficult, but I have

a few thoughts. The first is that humans appear to have some need to

look down on someone; there’s just a basic tribalistic impulse in all of

us. And if you’re an elite white professional, working class whites

are an easy target: you don’t have to feel guilty for being a racist or a

xenophobe. By looking down on the hillbilly, you can get that high of

self-righteousness and superiority without violating any of the moral

norms of your own tribe. So your own prejudice is never revealed for

what it is.

A lot of it is pure disconnect–many

elites just don’t know a member of the white working class. A professor

once told me that Yale Law shouldn’t accept students who attended state

universities for their undergraduate studies. (A bit of background:

Yale Law takes well over half of its student body from very elite

private schools.) “We don’t do remedial education here,” he said. Keep

in mind that this guy was very progressive and cared a lot about income

inequality and opportunity. But he just didn’t realize that for a kid

like me, Ohio State was my only chance–the one opportunity I had to do

well in a good school. If you removed that path from my life, there was

nothing else to give me a shot at Yale. When I explained that to him,

he was actually really receptive. He may have even changed his mind.

What does it mean for our politics? To

me, this condescension is a big part of Trump’s appeal. He’s the one

politician who actively fights elite sensibilities, whether they’re good

or bad. I remember when Hillary Clinton casually talked about putting

coal miners out of work, or when Obama years ago discussed working class

whites clinging to their guns and religion. Each time someone talks

like this, I’m reminded of Mamaw’s feeling that hillbillies are the one

group you don’t have to be ashamed to look down upon. The people back

home carry that condescension like a badge of honor, but it also hurts,

and they’ve been looking for someone for a while who will declare war on

the condescenders. If nothing else, Trump does that.

This is where, to me, there’s a lot of

ignorance around “Teflon Don.” No one seems to understand why

conventional blunders do nothing to Trump. But in a lot of ways, what

elites see as blunders people back home see as someone

who–finally–conducts themselves in a relatable way. He shoots from the

hip; he’s not constantly afraid of offending someone; he’ll get angry

about politics; he’ll call someone a liar or a fraud. This is how a lot

of people in the white working class actually talk about politics, and

even many elites recognize how refreshing and entertaining it can be!

So it’s not really a blunder as much as it is a rich, privileged Wharton

grad connecting to people back home through style and tone. Viewed

like this, all the talk about “political correctness” isn’t about any

specific substantive point, as much as it is a way of expanding the

scope of acceptable behavior. People don’t want to believe they have to

speak like Obama or Clinton to participate meaningfully in politics,

because most of us don’t speak like Obama or Clinton.

On the other hand, as Hillbilly Elegy

says so well, that reflexive reverse-snobbery of the hillbillies and

those like them is a real thing too, and something that undermines their

prospects in life. Is there any way for it to be overcome, other than

getting out of the bubble, as you did?

I’m not sure we can overcome it entirely.

Nearly everyone in my family who has achieved some financial success

for themselves, from Mamaw to me, has been told that they’ve become “too

big for their britches.” I don’t think this value is all bad. It

forces us to stay grounded, reminds us that money and education are no

substitute for common sense and humility. But, it does create a lot of

pressure not to make a better life for yourself, and let’s face it: when

you grow up in a dying steel town with very few middle class job

prospects, making a better life for yourself is often a binary

proposition: if you don’t get a good job, you may be stuck on welfare

for the rest of your life.

I’m a big believer in the power to change

social norms. To take an obvious recent example, I see the decline of

smoking as not just an economic or regulatory matter, but something our

culture really flipped on. So there’s value in all of us–whether we

have a relatively large platform or if our platform is just the people

who live with us–trying to be a little kinder to the kids who want to

make a better future for themselves. That’s a big part of the reason I

wrote the book: it’s meant not just for elites, but for people from my

own clan, in the hopes that they’ll better appreciate the ways they can

help (or hurt) their own kin.

At the same time, the hostility between

the working class and the elites is so great that there will always be

some wariness toward those who go to the other side. And can you blame

them? A lot of these people know nothing but judgment and condescension

from those with financial and political power, and the thought of their

children acquiring that same hostility is noxious. It may just be the

sort of value we have to live with.

The odd thing is, the deeper I get into

elite culture, the more I see value in this reverse snobbery. It’s the

great privilege of my life that I’m deep enough into the American elite

that I can indulge a little anti-elitism. Like I said, it keeps you

grounded, if nothing else! But it would have been incredibly

destructive to indulge too much of it when I was 18.

I live in the rural South now, where I

was born, and I see the same kind of social pathologies among some poor

whites that you write about in Hillbilly Elegy. I also see the

same thing among poor blacks, and have heard from a few black friends

who made it out as you did the same kind of stories about how their own

people turned on them and accused them of being traitors to their family

and class — this, only for getting an education and building stable

lives for themselves. The thing that so few of us either understand or

want to talk about is that nobody who lives the way these poor black and

white people do is ever going to amount to anything. There’s never

going to be an economy rich enough or a government program strong enough

to compensate for the lack of a stable family and the absence of

self-discipline. Are Americans even capable of hearing that anymore?

Judging by the current political

conversation, no: Americans are not capable of hearing that anymore. I

was speaking with a friend the other night, and I made the point that

the meta-narrative of the 2016 election is learned helplessness as a

political value. We’re no longer a country that believes in human

agency, and as a formerly poor person, I find it incredibly insulting.

To hear Trump or Clinton talk about the poor, one would draw the

conclusion that they have no power to affect their own lives. Things

have been done to them, from bad trade deals to Chinese labor

competition, and they need help. And without that help, they’re doomed

to lives of misery they didn’t choose.

Obviously, the idea that there aren’t

structural barriers facing both the white and black poor is ridiculous.

Mamaw recognized that our lives were harder than rich white people, but

she always tempered her recognition of the barriers with a hard-noses

willfulness: “never be like those a–holes who think the deck is stacked

against them.” In hindsight, she was this incredibly perceptive woman.

She recognized the message my environment had for me, and she actively

fought against it.

There’s good research on this stuff.

Believing you have no control is incredibly destructive, and that may be

especially true when you face unique barriers. The first time I

encountered this idea was in my exposure to addiction subculture, which

is quite supportive and admirable in its own way, but is full of

literature that speaks about addiction as a disease. If you spend a day

in these circles, you’ll hear someone say something to the effect of,

“You wouldn’t judge a cancer patient for a tumor, so why judge an addict

for drug use.” This view is a perfect microcosm of the problem among

poor Americans. On the one hand, the research is clear that there are

biological elements to addiction–in that way, it does mimic a disease.

On the other hand, the research is also clear that people who believe

their addiction is a biologically mandated disease show less ability to

resist it. It’s this awful catch-22, where recognizing the true nature

of the problem actually hinders the ability to overcome.

Interestingly, both in my conversations

with poor blacks and whites, there’s a recognition of the role of better

choices in addressing these problems. The refusal to talk about

individual agency is in some ways a consequence of a very detached

elite, one too afraid to judge and consequently too handicapped to

really understand. At the same time, poor people don’t like to be

judged, and a little bit of recognition that life has been unfair to

them goes a long way. Since Hillbilly Elegy came out, I’ve gotten so many messages along the lines of: “Thank you for being sympathetic but also honest.”

I think that’s the only way to have this

conversation and to make the necessary changes: sympathy and honesty.

It’s not easy, especially in our politically polarized world, to

recognize both the structural and the cultural barriers that so many

poor kids face. But I think that if you don’t recognize both, you risk

being heartless or condescending, and often both.

On the other hand, as a conservative, I

grow weary of fellow middle-class conservatives acting as if it were

possible simply to bootstrap your way out of poverty. My dad was able to

raise my sister and me in the 1970s on a civil servant’s salary,

supplemented by my mom’s small salary as a school bus driver. I doubt

this would be possible today. You’re a conservative who has known

poverty and powerlessness as well as wealth and privilege. What do you

have to say to your fellow conservatives?

I think you hit the nail right on the

head: we need to judge less and understand more. It’s so easy for

conservatives to use “culture” as an ending point in a discussion–an

excuse to rationalize their worldview and then move on–rather than a

starting point. I try to do precisely the opposite in Hillbilly Elegy. This book should start conversations, and it is successful, it will.

The Atlantic‘s Ta-Nehisi Coates,

who I often disagree with, has made a really astute point about culture

and the way it has been deployed against the black poor. His point,

basically, is that “culture” is little more than an excuse to blame

black people for various pathologies and then move on. So it’s hardly

surprising that when poor people, especially poor black folks, hear

“culture,” they instinctively run for the hills.

But let’s just think about what culture

really means, to borrow an example from my life. One of the things I

mention in the book is that domestic strife and family violence are

cultural traits–they’re just there, and everyone experiences them in one

form or another. I learned domestic strife from the moment I was born,

from more than 15 stepdads and boyfriends I encountered, to the

domestic violence case that nearly tore my family apart (I was the

primary victim). So predictably, by the time I got married, I wasn’t a

great spouse. I had to learn, with the help of my aunt and sister (both

of whom had successful marriages), but especially with the help of my

wife, how not to turn every small disagreement into a shouting match or a

public scene. Too many conservatives look at that situation, say “well

that’s a cultural problem, nothing we can do,” and then move on.

They’re right that it’s a cultural problem: I learned domestic strife  from my mother, and she learned it from her parents.

from my mother, and she learned it from her parents.

But to speak “culture” and then move on

is a total copout, and there are public policy solutions to draw from

experiences like this: how could my school have better prepared me for

domestic life? how could child welfare services have given me more

opportunities to spend time with my Mamaw and my aunt, rather than

threatening me–as they did–with the promise of foster care if I kept

talking? These are tough, tough problems, but they’re not totally

immune to policy interventions. Neither are they entirely addressable

by government. It’s just complicated.

That’s just one small example, obviously,

and there are many more in the book. But I think this unwillingness to

deal with tough issues–or worse, to pretend they’ll all go away if we

can hit 4 percent growth targets–is a significant failure of modern

conservative politics. And looking at the political landscape, this

failure may very well have destroyed the conservative movement as we

used to know it.

And what do you have to say to liberals?

Well, it’s almost the flip side: stop

pretending that every problem is a structural problem, something imposed

on the poor from the outside. I see a significant failure on the Left

to understand how these problems develop. They see rising divorce rates

as the natural consequence of economic stress. Undoubtedly, that’s

partially true. Some of these family problems run far deeper. They see

school problems as the consequence of too little money (despite the

fact that the per pupil spend in many districts is quite high), and

ignore that, as a teacher from my hometown once told me, “They want us

to be shepherds to these kids, but they ignore that many of them are

raised by wolves.” Again, they’re not all wrong: certainly some schools

are unfairly funded. But there’s this weird refusal to deal with the

poor as moral agents in their own right. In some cases, the best that

public policy can do is help people make better choices, or expose them

to better influences through better family policy (like my Mamaw).

There was a huge study that came out a

couple of years ago, led by the Harvard economist Raj Chetty. He found

that two of the biggest predictors of low upward mobility were 1) living

in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty and 2) growing up in a

neighborhood with a lot of single mothers. I recall that some of the

news articles about the study didn’t even mention the single mother

conclusion. That’s a massive oversight! Liberals have to get more

comfortable with dealing with the poor as they actually are. I admire

their refusal to look down on the least among us, but at some level,

that can become an excuse to never really look at the problem at all.

In Hillbilly Elegy, I noticed

the parallel between two disciplined forms of life that enabled you and

your biological father to transcend the chaos that dragged down so many

others y’all knew. You had the US Marine Corps; he had fundamentalist

Christianity. How did they work inner transformation within you both?

Well, I think it’s important to point out

that Christianity, in the quirky way I’ve experienced it, was really

important to me, too. For my dad, the way he tells it is that he was a

hard partier, he drank a lot, and didn’t have a lot of direction. His

Christian faith gave him focus, forced him to think hard about his

personal choices, and gave him a community of people who demanded, even

if only implicitly, that he act a certain way. I think we all

understate the importance of moral pressure, but it helped my dad, and

it has certainly helped me! There’s obviously a more explicitly

religious argument here, too. If you believe as I do, you believe that

the Holy Spirit works in people in a mysterious way. I recognize that a

lot of secular folks may look down on that, but I’d make one important

point: that not drinking, treating people well, working hard, and so

forth, requires a lot of willpower when you didn’t grow up in

privilege. That feeling–whether it’s real or entirely fake–that there’s

something divine helping you and directing your mind and body, is

extraordinarily powerful.

General Chuck Krulak, a former commandant

of the Marine Corps, once said that the most important thing the Corps

does for the country is “win wars and make Marines.” I didn’t

understand that statement the first time I heard it, but for a kid like

me, the Marine Corps was basically a four-year education in character

and self-management. The challenges start small–running two miles, then

three, and more. But they build on each other. If you have good

mentors (and I certainly did), you are constantly given tasks, yelled at

for failing, advised on how not to fail next time, and then given

another try. You learn, through sheer repetition, that you can do

difficult things. And that was quite revelatory for me. It gave me a

lot of self-confidence. If I had learned helplessness from my

environment back home, four years in the Marine Corps taught me

something quite different.

The other thing the Marine Corps did is

hold our hands and prevent us from making stupid decisions. It didn’t

work on everyone, of course, but I remember telling my senior

noncommissioned officer that I was going to buy a car, probably a BMW.

“Stop being an idiot and go get a Honda.” Then I told him that I had

been approved for a new Honda, at the dealer’s low interest rate of 21.9

percent. “Stop being an idiot and go to the credit union.” He then

ordered another Marine to take me to the credit union, open an account,

and apply for a loan (the interest rate, despite my awful credit, was

around 8 percent). A lot of elites rely on parents or other networks

the first time they made these decisions, but I didn’t even know what I

didn’t know. The Marine Corps ensured that I learned.

Finally, what did watching Donald

Trump’s speech last night make you think about this fall campaign, and

the future of the country?

Well, I think the speech itself was a

perfect microcosm of why I love and am terrified of Donald Trump. On

the one hand, he criticized the elites and actually acknowledge the hurt

of so many working class voters. After so many years of Republican

politicians refusing to even talk about factory closures, Trump’s

message is an oasis in the desert. But of course he spent way too much

time appealing to people’s fears, and he offered zero substance for how

to improve their lives. It was Trump at his best and worst.

My biggest fear with Trump is that,

because of the failures of the Republican and Democratic elites, the bar

for the white working class is too low. They’re willing to listen to

Trump about rapist immigrants and banning all Muslims because other

parts of his message are clearly legitimate. A lot of people think

Trump is just the first to appeal to the racism and xenophobia that were

already there, but I think he’s making the problem worse.

The other big problem I have with Trump

is that he has dragged down our entire political conversation. It’s not

just that he inflames the tribalism of the Right; it’s that he

encourages the worst impulses of the Left. In the past few weeks, I’ve

heard from so many of my elite friends some version of, “Trump is the

racist leader all of these racist white people deserve.” These comments

almost always come from white progressives who know literally zero

culturally working class Americans. And I’m always left thinking: if

this is the quality of thought of a Harvard Law graduate, then our

society is truly doomed. In a world of Trump, we’ve abandoned the

pretense of persuasion. The November election strikes me as little more

than a referendum on whose tribe is bigger.

But I remain incredibly optimistic about

the future. Maybe that’s the hillbilly resilience in me. Or maybe I’m

just an idiot. But if writing this book, and talking with friends and

strangers about its message, has taught me anything, it’s that most

people are trying incredibly hard to make it, even in this more

complicated and scary world. The short view of our country is that

we’re doomed. The long view, inherited from my grandparents’ 1930s

upbringing in coal country, is that all of us can still control some

part of our fate. Even if we are doomed, there’s reason to pretend

otherwise.

—

UPDATE: Best e-mail I’ve yet received about this interview:

Mr Dreher, I am writing to thank you for the impressive

and thoughtful interview of JD Vance on his book. I am not a

conservative. I am a black, gay, immigrant who has been blessed by the

dynamic and productive American society we live in. So I am not the

average reader of the American Conservative. I came to your article

through a friend. So I just wanted to share how refreshing I found to

have two white men being able to speak about class, their family

experience and acknowledging an experience that is often not visible in

our society. The poor rural south that you described and the communities

that Mr.. Vance write about are familiar to me. Born in Haiti, growing

up in Congo, Africa. I recognize that poverty, I recognize the

marginalization and I SO APPRECIATED the conversation about individual

agency! That is ultimately where the American dream (if it exists)

lives. That deep belief that I as an individual am not a victim and can

engage with the world around me! That has been my American lesson. That

is the source of the dynamism of this society! Thank you!