"Opt-out here was so big that it really shook the system," says the DOE insider. "If we were to increase that number this year, it has the potential to bring their whole crazy system down."...Village VoiceAnd yes Virginia, our own union leaders in Unity Caucus are

working like little beavers to help keep their whole crazy system up and going. Kate Taylor in the NY Times wrote a few days ago:

Teachers Are Warned About Criticizing New York State Tests .... Kate Taylor, NY Times

Since the revolt by parents against New York State’s reading and math tests last year, education officials at the state level have been bending over backward to try to show that they are listening to parents’ and educators’ concerns.The tests, which are given to third through eighth graders and will begin this year on April 5, were shortened, time limits were removed, and the results will not be a factor in teacher evaluations, among other changes.On Monday, Betty A. Rosa, the newly elected chancellor of the Board of Regents and the state’s highest education official, even said that if she had children of testing age, she would have them sit out the exams.The message, clearly, is: We hear you.But in New York City, the Education Department seems to be sending a different message to some teachers and principals: Watch what you say.At a forum in December, Anita Skop, the superintendent of District 15 in Brooklyn, which had the highest rate of test refusals in the city last year, said that for an educator to encourage opting out was a political act and that public employees were barred from using their positions to make political statements.

The response of MORE activists has basically been "FU, Come and get me."

The response from the UFT has not been outrage at these gag orders but telling teachers they would not defend them.

MORE VP candidate for elem school Lauren Cohen is the chapter leader at PS 321

MORE VP candidate for elem school Lauren Cohen is the chapter leader at PS 321

At Public School 321 in Park Slope, Brooklyn, part of District 15, more than a third of the eligible students did not sit for the tests last year, and the principal, Elizabeth Phillips, has in the past been outspoken in opposing them.At a PTA meeting there last week, Ms. Phillips was studiedly neutral, but several teachers criticized the tests, with one comparing the stand against them to abolitionism and the fight for same-sex marriage.

I wonder how the opt-out issue will play out in the UFT elections. Will teachers who feel repressed and gagged and unsupported by their union over a fundamental free speech issue be aware enough to link the MORE campaign to that issue especially with so visible an opt out candidate as Jia Lee? The election timing in May with the tests a hot topic may well be a factor. Will kids vomiting on their high stakes tests have an impact?

One of our newer MORE members came down from the DA last week shocked that the Unity Caucus leadership supports testing, evaluations based on testing and undermines the opt out movement.

I told her that fundamentally our union leaders are ed deformers light and philosophically have always supported testing and VAM and holding teachers accountable -- sometimes you just have to wade through the distracting rhetoric to see their path clearly.

MORE unequivocally supports opt out and many of the teachers stand up openly in defiance: Katie Lapham, Jia Lee, Lauren Cohen, Michelle Baptiste are just a few examples.

MORE UFT election candidate for AFT/NYSUT delegate John Antush has a piece in Monthly Review:

Should New York City Teachers Support Opt Out? Two Views in the UFT

President Michael Mulgrew and his entrenched Unity caucus supported the CCSS and standardized testing, including the use of student test scores as part of teacher evaluations, and refused to support Opt Out. At the 2014 convention of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), Mulgrew harangued educators that “The [Common Core State] standards are ours. Tests are ours.” He intoned: “If someone takes something from me, I’m going to grab it right back outta their cold twisted sick hand and say ‘that’s mine!’ You do not take what is mine! And I’m gonna punch you in the face and push you in the dirt.… These are our tools! And you sick people need to be away from us and the children that we teach.”2Meanwhile, rank-and-file UFTers in the MORE-UFT (Movement of Rank and File Educators) caucus and other groups joined the city’s Opt Out movement as part of the struggle against “ed deform.”3 Jia Lee, as a “Teacher of Conscience,” publicly refused to administer high-stakes tests starting in 2014. She continues to educate school communities about opt-out rights and speaks out for the city’s movement.Let's be clear which forces oppose opt-out.

- Ed deformers of all types because opt out denies them the data they want to manipulate to undermine public education. You won't find E4E supporting opt-out though they will use some deflection to act neutral.

- UFT/AFT/NYSUT - historical context

- UFT pals Farina and state ed comm Elia

Parents are fighting back:Chalkbeat: Fariña says opting out is OK, in a few cases

opt-out answers

Chancellor Carmen Fariña told opt-out leaders that she would keep her child from taking state tests in two instances — as a new immigrant and if her child was receiving special education services. DNAinfo, New York Post

After Regents Chancellor-elect Betty Rosa said she would opt her own child out of state tests, Commissioner MaryEllen Elia has been working to assure superintendents that the two are on the same page about tests. Chalkbeat

As opt-out debates continue, state’s top education officials work to stay united

Commissioner MaryEllen Elia told regional leaders last week that she and Betty Rosa have a "shared view" on state assessments. But Elia has said it is unethical for educators to encourage the testing boycott — and Rosa seemed to do so just after being chosen as Regents chancellor. Read more.

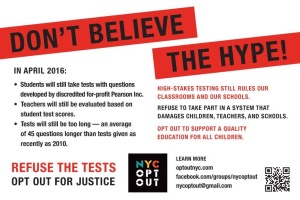

carrie (for NYCOO)Calling all NYC parents:Thank you!

Have you been sent a letter from your school leaders that has inaccurate info about testing or opt out? Has a teacher or administrator denied your request to opt out?

If you or someone you know has had difficulty opting opt for any reason, please contact us at nycoptout@gmail.com.

We'd love to see any letters or documentation you have, if available. And we will keep sources anonymous if preferred.

Low-Income Parents Are Caught Between the Growing Opt-Out Movement and the City’s Attempts to Clamp Down on Dissent

http://www.villagevoice.com/news/low-income-parents-are- caught-between-the-growing- opt-out-movement-and-the-city- s-attempts-to-clamp-down-on- dissent-8447023

If you needed a sign that the reported détente in the ongoing war over New York's annual public school tests wasn't all it was cracked up to be, it might have come earlier this month. That's when news broke of Southside Williamsburg principal Sereida Rodriguez-Guerra berating a fifth-grader who'd passed out materials about refusing to take the standardized state exams. "You've got to get this opt-out stuff out of your head!" Rodriguez-Guerra snapped at the assembled student body. For his part, the eleven-year-old was sent to her office, where he burst into tears.

Since more than 200,000 school kids statewide refused last spring to take the tests — six-day affairs that are, depending on your perspective, either the perfect tool for holding failing schools accountable, or the death of public education itself — government officials have been in damage-control mode, trying to stave off an even wider revolt: MaryEllen Elia, who'd replaced former state education commissioner (and now Obama education secretary) John King after he enraged anti-testing parents by dismissing them as "co-opted by special interests," lifted the time limit on tests in January, saying she hoped it would reduce "stresses" on test-taking kids. The state board of regents, meanwhile, placed a four-year moratorium on using results to grade teachers, then selected a new chancellor, Bronx educator Betty Rosa (who immediately declared that if she were a parent, she'd opt her kids out).

But down in the trenches it's been a different story. As city third- through eighth-graders ready their No. 2 pencils for next week's kickoff of test season, numerous parents and educators say that battles are only heating up between critics of high-stakes testing and state and city officials who want to stuff the opt-out genie back in the bottle. Pressures are particularly high in the low-income schools in black and Latino neighborhoods that both sides in the opt-out debates see as the next battleground.

"The city department of education is threatening principals both directly and indirectly" over speaking out on the tests, says Jamaal Bowman, a Bronx principal who has nonetheless taken it upon himself to speak to parents at several low-income outer-borough schools about their opt-out rights. Ever since Elia, in one of her less conciliatory moments, declared last summer that opting out was "not reasonable" and "unethical" for teachers and other educators to support, he says, school officials have been making it increasingly difficult for parents in many neighborhoods to even find out their options.

In this light, the meltdown by P.S.84's Rodriguez-Guerra, previously lauded as a bridge-builder who spoke out against "teaching to the test," seems less like an aberration than the tip of an iceberg. When added to the pressures that low-performing schools already face in the age of school accountability, the stepped-up anti-opt-out campaign amounts to "psychological warfare," says one staffer who works on testing and teacher evaluations for the central city Department of Education office, and who asked not to be identified for fear of retribution.

"Opt-out here was so big that it really shook the system," says the DOE insider. "If we were to increase that number this year, it has the potential to bring their whole crazy system down."

The modern regime of public school testing got its start, like so many other dubious realities of 21st-century life, from the pen of George W. Bush. In 2001, the newly elected president signed the No Child Left Behind Act, which optimistically dictated that every student in every school in the nation be made "proficient" in math and reading for their grade level — and ordered states to impose new tests to gauge their progress.

To write its tests, New York State turned to British testing giant Pearson, which immediately earned parents' ire for baffling questions: The infamous comprehension question on the 2012 eighth-grade reading exam about a talking pineapple that challenged a hare to a race and was eventually eaten became an instant classic; Louis CK's instantly viral tweet, "My kids used to love math! Now it makes them cry," pretty well summed up public reaction. Teachers, barred from revealing any details of the tests, took to online discussion boards to gripe about the process: "Two students raised their hands to tell me that a sentence didn't make sense," went one typical comment. "I had to agree with them."

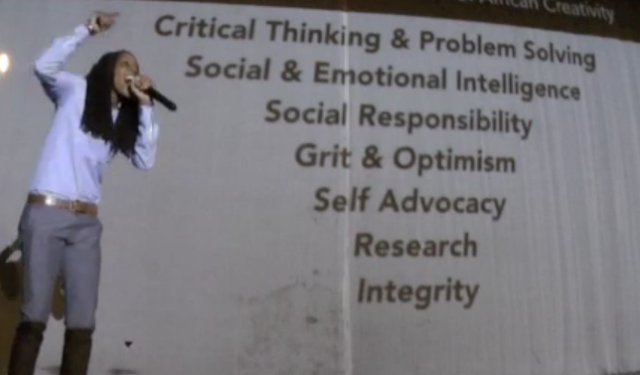

Yet the problem with New York's tests, insist opt-out proponents, isn't how well or poorly they're worded, but how they warp the entire educational system. Bowman is quick to say he doesn't have a problem with tests per se and that his school, the Cornerstone Academy for Social Action Middle School in the Eastchester section of the Bronx, uses plenty of in-house assessments to gauge students' individual strengths and weaknesses. Rather, his concern is about so-called "high stakes" tests, where results are used for everything from determining whether students advance to the next grade to teacher firings and school closings.

Such tests, critics argue, turn the educational experience into a massive exercise in gaming the system. (In testing circles, this is known as Campbell's Law, named for a social psychologist who theorized in 1976 that the more a test affects important decisions, the more likely it is to lead to corruption.) At its most mundane, this can lead schools to spend the bulk of the year teaching to the test and students to learn how to parrot the formulaic five-paragraph essays that score well on test-graders' rubrics. At its worst, it can encourage behavior like that of Harlem elementary school principal Jeanene Worrell-Breeden, who took it upon herself to falsify student test answers last spring — and who, when caught, threw herself in front of a subway train.

For all this, says Columbia Teachers College professor Aaron Pallas, who has written extensively on high-stakes testing, the tests may not even accomplish what they set out to do. "They aren't much help in determining whether a school is a good school or a teacher is a good teacher," he says, or even necessarily a good predictor of students' future performance. (While the state calibrates the tests to ensure that proper percentages of students earn passing grades, it hasn't released any studies of whether the scores are a valid measure of students' actual learning.) "I do think that Commissioner Elia is saying more of the things that parents and educators want to hear." But none of the new measures, he says, changes high-stakes tests' biggest problem, which is that they're trying to solve multiple problems with a single blunt instrument.

"Why are we engaged in this process?" asks Pallas. "Is it to try to identify precisely for individual students whether they're above the bar or not? Is it to try to provide feedback to teachers about what students know in a timely way to help them revise their instruction? Is it, as it has been in the past, to try to hold schools and teachers accountable for students' performance? What the ideal testing system might look like will vary depending on the purpose."

Most of the initial testing uproar was centered in the sections of New York that might be called the Louis CK districts. An opt-out map published last summer by education news site Chalkbeat revealed red dots — marking schools where over 20 percent of students opted out — marching down through Manhattan and halting in brownstone Brooklyn, with the outer boroughs largely untouched. That demographic pattern was largely replicated at the state level: Over 20 percent of parents statewide opted out, mostly on Long Island and in majority-white counties upstate, but only 1.4 percent in the city. Those numbers have helped feed the belief that, as then–U.S. education secretary Arne Duncan proclaimed in 2013, the opt-out movement consists of "white suburban moms who — all of a sudden — [worry that] their child isn't as brilliant as they thought they were, and their school isn't quite as good as they thought they were."

Duncan's suggestion that opt-out is a white helicopter-parent phenomenon drives Jamaal Bowman up the wall. Sure, opt-out numbers may be low in African-American neighborhoods, he says, but that may well be because "many parents are not aware they have the right to refuse the state exam." After all, the City Council unanimously passed a resolution last year calling on the DOE to include opt-out information in its Parents' Bill of Rights, only to see that request ignored by Schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña. Bowman's responsibility, as he sees it, is to raise awareness: "We've focused so much on annual standardized tests that we're not focused on what research says works to close the achievement gap" for black and Latino school kids.

Continuing to conduct business this way, he says, is "educational malpractice." For Bowman, that's putting it mildly: Last year, noting the continued educational gaps by race despite increasing numbers of assessments, he called standardized tests "a form of modern-day slavery."

On one of Bowman's first testing-talk visits, to P.S.219 in the Remsen Village section of Brownsville earlier this month, families slowly trickled in. "Waiting for the magic number — that fifth person," he declared as the 6:30 start time ticked by. "You can start a revolution with five."

Bowman's spiel that night delved deep into the history of high-stakes tests, tracing them from their origin in No Child Left Behind through Mayor Bloomberg's "accountability" push ("if I didn't teach to the test, I may be liable to lose my job"). Parents sat up straighter when he put up a slide showing the dramatic racial disparities in test results: over 50 percent proficiency for white and Asian elementary and middle schoolers; under 20 percent for blacks and Latinos.

"While our kids are taking these tests, private school kids are creating the next smartphone, and then our kids are going to work for them," he proclaimed, to a chorus of mmm-hmms.

The crowd had filled in by then, and parents had plenty of questions and complaints: What were the risks to their kids or their school if they opted out? Why weren't test scores available until September, by which point kids might have already been held back for summer school?

Rhonda Joseph, a parent at nearby P.S.268 who serves on the District 18 Community Education Council, reported that the district superintendent had told her that parents who wanted to opt out needed to have asked their children's teachers to start building a portfolio of student work back in September to use as an alternate evaluation — sparking a lively debate about how to ensure that students will advance to the next grade. (All teachers should have portfolio information on hand, say schools experts.)

P.S.219 parent Tamika Howell explained she'd rushed over to the meeting from work because she was worried that her son, now in fourth grade, should be doing better in school and the tests didn't seem to be helping. "I couldn't get the score until he started back in September," she recalled, and even then "all we got was just the grade — it didn't say where his weak points were, it didn't tell you where his strong points are, if he needs more help." Bowman's presentation, she said, had been very useful: "Most of us were scared to opt out, because we don't know what our rights are. We think if we opt out, maybe the school's going to be penalized, my child may be penalized."

A few blocks east on Brownsville's Riverdale Avenue, P.S.446 is one of the outliers on the opt-out map — though far outside the anti-testing heartland, it posted a refusal rate of greater than 70 percent for the past two years, one of the highest in the state. Kerryann Bowman, a former PTA president and parent of a fourth-grader, says the opt-out push there was launched by school parents after they made contact with parent organizers from Brooklyn New School in Carroll Gardens. "As a parent, I don't believe the test is fair," says Bowman (no relation to Jamaal Bowman). "If it was a part of your regular curriculum, then I could see — test them on what they know. But if it's a completely different thing, and you only prep them for two months, I don't think it's fair."

P.S.219 parent coordinator Anthony Gordon, who'd invited Jamaal Bowman to conduct his testing forum after finding him on Twitter, says that parents there "have always been concerned with this high-stakes testing." But, he adds, some may have been scared off when the NAACP and other civil rights groups issued a statement warning that it could "sabotage important data and rob us of the right to know how our students are faring" if too many families opted out. "I don't know if Bill Gates or someone got to them," he quips.

Gordon is quick to add that he's officially agnostic on whether parents should opt their kids out of the tests. "It's not like I'm for or against," he says. "But as a parent coordinator, if a parent asks me, 'What do you know about this?' that's part of the job. You have to let them know what's going on."

In many ways, the testing battle has turned into a war over information. But information is not always quick to trickle down, especially in poorer schools with fewer ties to the opt-out push.

At P.S.446, for example, where 70 percent of kids did not take the tests and parents continue organizing to opt out, the school administration has clammed up. Principal Meghan Dunn would not accept a Voice request for an interview, while parent coordinator Christina Yancey replied to multiple phone calls and emails with a single text: "We do not have an opt out campaign at our school. So we probably shouldn't be in the article."

Multiple sources in the city education system say responses like these are likely the result of a high-pressure state and city campaign to clamp down on educators who might publicly criticize the tests. The pushback began last summer, when, shortly after Elia's comment that teachers' trash-talking the testing was "unethical," the New York State Education Department launched a "toolkit" for superintendents to make their own statements on the subject: Sample talking points included that the state tests "help ensure that students graduate ready to handle college coursework and 21st-century careers" and "ensure that traditionally underserved students...are not overlooked." It even provided sample tweets for educators to use in support of the tests.

(Asked how educators should use the blatantly pro-test materials if they weren't supposed to take sides on the test, a department spokesperson replied only, "The toolkit is intended to help superintendents communicate with parents and educators in their districts about the value and importance of the annual Grades 3–8 English Language Arts and Math Tests.")

Asked if the city DOE had stepped up pressure on educators to toe the line, spokesperson Devora Kaye points to Chancellor Fariña's open letter to principals on March 15, in which she spelled out changes being made to this year's tests to help "create supportive environments which allow all students to reach their greatest potential." Kaye adds, "We've encouraged schools to work with their parent coordinator to facilitate conversations with students' families to address any questions they may have."

But multiple principals and other educators — mostly speaking to the Voice on condition of anonymity — say that the actual directives from Fariña's office this year have been closer to a gag order. "I can tell you, every day I talk to principals who are fed up, frustrated, furious, and completely confused by the system, but no one can say anything," says the DOE insider. "I know examples where really wonderful principals who spoke out bravely the year before were specifically called upon and told, 'If you talk, you won't get tenure.' "

In one much-discussed video, District 15 superintendent Anita Skop was asked at a public forum last December if educators could share their concerns about the tests with parents. "They shouldn't," she replied, "because they have no right to say, 'This is how I feel.' They have no right. It's not their job." Skop continued, "No person who is a public figure can use their office as a bully pulpit to espouse any political perspective, whether it's telling who to select for mayor or whether or not you should opt your children out of the tests." That sent a clear message to principals like P.S.321's Liz Phillips, who had penned a New York Times op-ed in 2014 calling the tests "confusing, developmentally inappropriate, and not well aligned with the Common Core standards."

Brooklyn New School's Anna Allanbrook, another District 15 principal who has been outspoken in support of parents' right to opt out, confirms that DOE officials told her in the fall that teachers should not speak to parents about the testing controversy. She also says she's heard from at least one other principal who caught flak from the DOE after her school community put out a statement in support of opting out, something she says is "definitely a different attitude" from past years.

What's causing this surge in principal-hushing isn't clear. One previously vocal elementary school principal, now speaking on condition of anonymity, suggests that recent changes at the state level — the moratorium on using test scores to grade teachers and the switch from the widely disliked King to the less antagonistic Elia — may have helped get the city on board, after Mayor de Blasio had previously vowed to "do everything in our power to move away from high-stakes testing," while saying of opting-out parents, "I understand their frustrations." The principal theorizes, "The city feels like they have a good relationship with the state right now, and that they are able to have some dialogue with the new commissioner."

For principals at low-income schools, meanwhile, the pressures don't end with a talking-to from their superintendent. Both in public and in private, they express concern about a federal rule that allows some Title I funding to be cut off if schools fail to reach 95 percent test compliance — a threat that's never been carried out but still sows fear.

And for those running low-performing schools, which tend to be concentrated in poor neighborhoods, equally worrisome have been the test-based Adequate Yearly Progress rankings that have been used to determine which schools will be placed into "receivership," effectively shutting them down and turning them over to new management. (Though the federal education bill passed in December eliminates AYP, many principals still fear their schools could be closed if too many families opt out.) For a school already on the bubble, the fear of fewer kids taking the tests — or worse, high-scoring kids disproportionately opting out, driving down average scores — can be enough, says the DOE insider, to scare a principal into toeing the testing line: "He's begging them to take that test because if they don't, there's a chance that the school will be put into receivership, and that for them is very real. It's a rough, class-based issue."

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the DOE's effort to clamp down on the flow of testing information is unlikely to affect schools in the opt-out belt: Principal Allanbrook says that though she and her staff have toned down their testing talk, most Brooklyn New School parents are already well-informed about the tests.

But in a city increasingly fractured along race and class lines, getting information on the tests can be extraordinarily frustrating. "My main source is the opt-out group," says Diane Tinsley, a fourth-grade parent and school leadership team member at Teachers College Community School, the Harlem elementary school whose principal committed suicide by subway last April. "It's so difficult to get information." Still, Tinsley says, she expects more opt-outs at her school this year in the wake of the scandal. At a recent panel discussion with the District 5 superintendent, she recalls, "I said, 'Maybe we can get the entire district to opt out!' She [the superintendent] almost fainted — she started saying, 'Oh, we can't do that!' "

"Nobody is really having forums in the community," complains Brownsville's Kerryann Bowman. Most public forums, she says, were "in places where you have to get on the train. And most of the district meetings are at night, when for most parents it's difficult to go to these meetings because you have children." She says she hopes that the testing debates can eventually be expanded to include disparities in both educational achievement and school funding levels.

That's the discussion that Jamaal Bowman hopes eventually to spark as well — not just opting out, but what parents and educators can opt in to. "We can do so many amazing, innovative things with our kids, and opt-out is step one to getting that process going," he says. When more than 200,000 parents opt out in one state, he continues, "that's saying some

thing. This is big, and it needs to get bigger."